THE installation of a new; “completely new,” chief by the people of Matabeleland living in Johannesburg provides us with an occasion so pregnant with the Janus metaphor. Janus is a two-faced Roman god of “beginnings and transitions, endings and time”.

Further, the most interesting aspect of this installation was not only the aesthetics, but the symbolic meaning contained in its narrative.

For decades now, the young people of Matabeleland have sought inspiration in the memory of the spears of their ancestors and the accompanying narratives of warrior exploits. As modern subjects, they have had to, in Kwame Nkrumah’s words, “face forward” dreaming of human rights and democracy.

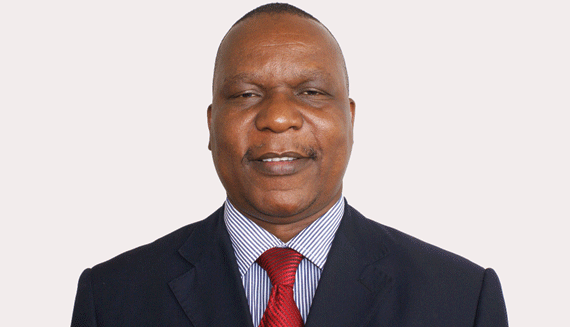

The installation of Albert Zwelibanzi Gumede as chief of the Ndebele in Johannesburg is one moment that disrupts this dialectical play between the past and the present. On one hand, it excites and gives those steeped in the hope of the renewal of the Ndebele nation, while on the other hand it offends others, especially those who consider themselves to be the custodians of ubuNdebele.

It is not largely the intention, let alone remit of this paper to engage the issues surrounding the “custodianship of ubuNdebele”, rather it is our intention to unpack the dialects of imagination aroused by this feat, particularly among the youths. The feat of this installation looms as a Janus moment beckoning us to reflect.

We need to understand the sort of moment in which this phenomenon is obtaining; because such “moments” are, to borrow Stuart Hall’s metaphor, “conjunctural” and have their historical specificity.

In that the institution of chieftainship among most African societies is an old institution that appeared before the Ndebele became a nation, even before Mzilikazi Khumalo became a king, the installation of Gumede as chief of the Ndebele in Johannesburg is old.

It is part of that human constructed primordial leadership tradition. This installation has some semblance of newness in that it breaks with the tradition of appointing chiefs in two ways; first, in that only the King appointed and installed new chiefs.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Secondly, it had become part of tradition that chiefs were only picked from patrilineal lineages left by King Mzilikazi and his son Lobengula; a tradition which can be traced back to kwaZulu. But given the exigencies of time and changing space, the novelty of the installation of Chief Gumede does not negate the past, but builds on it.

Like all chieftainships, it is a human invention at a certain historical “junction” to serve specific leadership purposes.

Admittedly, those grappling with the Matabeleland question; notions of uMthwakazi, what it means to be Ndebele and issues of being and belonging, are filled with ambivalence.

This ambivalence about the installation of Chief Gumede is a result of living between seemingly “primordial” ethno-politics accompanied by or hinged on ethno-practice and the social constructions of modern imaginaries. On one hand, the installation shows the guts of the young people to break with the past and invent their own chiefs.

This should be seen as young people’s hunger to “invent their own gods” as there is nothing “natural” about chieftainship. It is simply man-made. On the other hand, it raises an uncomfortable question on why would young people seem keen on the continuity of the chieftainship institution that has been so problematic over the years.

Chieftainship has never been a democratic leadership system. Since the Khumalo kings were deposed by colonialism, chieftainship has become a tool of “disciplining” the Ndebele in the hands of Rhodesian and Zimbabwean rulers, in that order.

Its continuity is dependent on political patronage on the side of Zanu PF and pride and sentimentality among the people of Matabeleland.

Beyond the ambivalence, Chief Gumede’s installation and the debates that have ensued provide a rich moment to think and rethink through several issues of national importance to the people of Matabeleland.

Of all the debates that have ensued — including, but not limited to that of the Kalanga nationalists fronted by Ndzimu-unami Emmanuel Moyo and that of Zapu elements — it is important to address the points raised by the “guardians of ubuNdebele.” The other debates are very important as well and space permitting, they must be addressed.

The royal Khumalos — and other traditionalists like Pathisa Nyathi — have to be helped to accept that Ndebele identity has for long been in a state of flux. What is apparent is that although the Ndebele identity, as a discursive social and historical construct, has evolved over years, it still longs to be in communion with the past.

In longing for continuity, this identity is Janus faced: mixing “primordiality” with modernity. The installation of Chief Gumede does not only occur within the context of the Diasporic and hegemonic Zimbabwean nationalism, but also within the context of the “dynamics” that have riddled the struggles of the peoples of Matabeleland, especially the youth and the women (the subaltern).

On one hand, it is a struggle of a migrant community for self-expression in a “foreign land” and a questioning of Zimbabwean nationalism — read through the spectacles of self-determination.

It is some kind of a homecoming for those from Matabeleland who view their presence in South Africa as a return to the land of their ancestors. On the other hand, home is not without its own challenges.

Chief among the challenges is the contentious issue of competing nationalisms —where Kalanga nationalism has clearly contested Nguni nationalism — and a dormant royal family creating a leadership vacuum since 1893. This is the “specificity” of the struggle of the subaltern of Matabeleland.

The struggle of the youth — both in the Diaspora and in the fatherland — is at the heart of the invention of the new chief — and pointing to the future of self-determination.

The installation of Gumede stands as part of a discourse or discourses around the path that the people of Matabeleland have travelled since 1893.

The question that sums up this struggle is one to do with how Chief Gumede’s installation will translate into a better future for a people who have had to endure genocide, loss of jobs, exile, famine, death of a culture and underdevelopment.

Like most subaltern struggles all over the world, the struggle of the youth of Matabeleland is on how to translate identity issues into bread and butter (economic) issues. The youth of Matabeleland have walked the path of unemployment, exile, labelling, arrests, persecution and suffering for years.

As a solution, they have even formed political parties that, consistent with underdog struggles, have fragmented. In an attempt to take their struggle to another level, Chief Gumede appears as a Leviathan figure to which these youths have entrusted their sovereignty as a people. For the Khumalos and others to reduce the whole thing to be about Chief Gumede is to miss the whole point, lose sight of the bigger picture and risk eternal irrelevance.

Khanyile Joseph Mlotshwa is a journalist and an MA student in Journalism and Media Studies at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa. Mphathisi Nkosisiphile Ndlovu is a Rhodes University MA graduate in Journalism and Media Studies.