MASERU — Two Zimbabwean journalists, and one Mosotho, have been banned from working in the media in Lesotho for a prescribed period after the High Court found them liable for violating their legal obligations to their employer who brought them from their native country to work in the Kingdom.

The landmark judgment, delivered by the Commercial Division of the High Court, dealt with issues of fiduciary duties of directors and unlawful competition.

It sets an important precedent against unethical directors and senior employees who, instead of doing the work that they are paid for by their employers (companies) and advancing the interests of the companies paying their remuneration, opting to spend time doing their own private work in direct competition with their employers without declaring their private interests first as required by law.

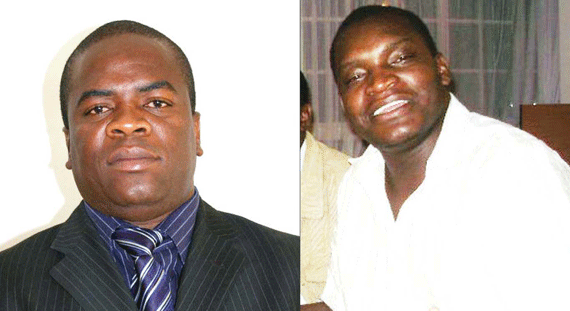

The two Zimbabweans, Abel Chapatarongo and Shakeman Mugari, and a Mosotho, Caswell Tlali, were sued by their now former employer, Africa Media Holdings Lesotho (AMH), the publishers of the Lesotho Times and the Sunday Express, who brought the two foreigners to Lesotho in 2008.

The two subsequently secretly set up their own company, Post Pty Ltd, whilst employed by AMH, in direct competition with their employer but without first declaring their interests.

This was despite that Chapatarongo had been promoted to become a full director and effectively running the business in the absence of its Chief Executive Officer, Basildon Peta, who is mainly based in Johannesburg, while Mugari was elevated to senior positions and became an ex-officio director by virtue of his seniority.

Tlali, a Mosotho, who was also in cohorts with Chapatarongo and Mugari, has also been banned for the year’s period prescribed in the judgment.

The three applicants in the matter, AMH, the Lesotho Times and Sunday Express, were originally granted an interim Interdict stopping Messrs Chapatarongo, Mugari, Tlali and the Post from operating in September 2013 after their plot against their employer was uncovered.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The Interdict has since been confirmed in the final judgment delivered by Justice Lebohang A. Molete over a week ago.

Peta, on behalf of AMH, the Lesotho Times and Sunday Express, submitted to court details of how he had been tipped by other staff members about how the three had been conspiring behind his back for some time to establish a rival company whilst still in the employment of the applicants.

Upon further investigations, Peta established that the plot was in fact true, particularly after they started resigning one by one beginning with Chapatarongo, the man Peta had mainly entrusted with running the businesses.

It became clear that while they were in the employment of AMH and its subsidiaries, and while they were being paid to advance their employer’s interests, the three men had been busy conspiring against the same employer who had paid their salaries for nearly 10 years in the case of Chapatarongo and for about half that timeframe for Mugari and Tlali.

It was argued in court that Chapatarongo and Mugari, had plotted to walk away with key staffers of their employer and to seek to severely undermine or destroy their employer first, to enable their new venture to succeed. Two senior staffers, including Tlali, assented to their plot.

Other staffers approached declined and some alerted Peta about how the time he was paying Chapatarongo and Mugari was being used for their own private interests.

Even after formalising their business and opening an office, Chapatarongo and Mugari attended key strategic meetings convened to plan for the future of AMH and its subsidiaries without declaring their interests. This automatically gave them access to their employer’s key plans and strategies knowing fully well that they had been plotting to set a rival company and would soon quit.

The court heard that Chapatarongo and Mugari did nothing to implement the strategic plans as instructed and generally neglected their duties while busy planning their own project.

Apart from publishing newspapers, AMH does contract publishing and produces journals, magazines, pamphlets and periodicals for clients.

Mugari, instead of mobilising and bringing this work to his employer as he was expected to do, was in fact approaching the applicants’ clients to get the business for himself, invoicing them and pocketing the money without the knowledge or permission from his employer.

It was further submitted in court that, during the entire long period that the three staffers had been conniving against their employer, their performances had drastically deteriorated.

Peta submitted, in his affidavit for the applicant companies, that some of the respondents’ work had in fact amounted to direct sabotage as he could not comprehend how such seasoned journalists could make the kind of errors that they were now producing.

The three had also harvested a number of lawsuits which were costing the company heavily in defending. They had further failed to produce strategic plans as directed, in addition to other failures.

Peta had ended up producing the strategic plans himself and tabled them at the meeting they attended without disclosing their interests in the other rival business they had established.

Judge Molete ruled that the three had breached their fiduciary duties and engaged in unlawful competition.

He agreed with counsel for the applicants, Advocate Philip Loubser, instructed by Neil Fraser of Webber and Newdigate, that the three had violated fiduciary duties as stipulated in common law and the provisions of the Companies Act of 2011 which penalises directors with jail terms of 10 years or fine of M50 000 or both for failing to declare their interests in a transaction or proposed transaction with a company.

“It should be obvious to any reasonable person that the plan of the Respondents was carefully conceived, planned and was finally ready to be implemented,” ruled Judge Molete.

“The initial stages must have been conceived long before the incorporation of the company (Post Pty Ltd) and the resignations.

They had to first approach and persuade people who would be part of the conspiracy, choose carefully the likely candidates and be convinced that they will keep the secret and not hesitate to resign from the employment of the applicants when called upon to do so,” read the judgment.

The judge noted that Mugari’s behaviour in sourcing private work from the applicants’ clients and billing them privately meant that he had, in fact, set himself up in competition with his own employer.

Yet his employer still paid his salary to bring the business to the employer as part of his duties. Even in doing that private work, Mugari used some of his employer’s staff and resources without authorisation and remunerated the staff privately from the proceeds he surreptitiously accrued from applicants’ clients.

“The respondents (Mugari, Chapatarongo and Tlali) not only used the time of the applicants to plot their sinister motives, they sought to lure the key personnel of the applicants, and to steal the clients as well. This surely constitutes unlawful competition,” ruled Judge Molete.

The judge said the conduct of the three in attending their employer’s critical strategic meetings without disclosing that they had already registered their own business to go into competition with their employer was wrong.

They had deliberately and unlawfully allowed themselves access to confidential information which they would use to advance their own interests and activities once they had left their employer.

Chapatarongo, Mugari and Tlali first tried to resort to legal technicalities (points in limine) to stop the case being heard in the courts on the merits. One such technicality was that Lesotho Times did not have a trader’s licence at the time of instituting legal proceedings and was thus operating “illegally” and should not be heard. But it was argued that this document had merely expired and was being renewed.

Judge Molete ruled that a “trading licence is neither a requirement nor a bar to institute an action or application nor to trading. It only carries penalties for non-compliance”.

A trader’s licence was renewed annually and “to suggest that the company must cease trading during the period of expiry of the last licence in order to restart after renewal of the licence would not make sense,” the judge ruled.

The judge admonished the respondents’ and their lawyers for their “lack of understanding” of the purpose and meaning of points in limine.

He referred to a case in which Court of Appeal Judge Michael Ramodibedi had criticised lawyers for increasingly raising “so called points in limine that are completely devoid of substance and (that are) nothing but total abuse of court process…..”

After failing on the technicalities or points in limine, the respondents had in their papers also sought to proceed on the merits by blaming their actions on their employer.

They had raised a lot of what Peta described as “scurrilous and outrageous” allegations. None of the mud they tried to throw at their employer seems to have stuck in court and Chapatarongo, Mugari, Tlali and the Post lost the case.

Advocate Philip Loubser, instructed by Neil Fraser of Webber and Newdigate represented AMH, the Lesotho Times and the Sunday Express. The respondents were represented by Advocates Koili Ndebele and Monaheng Rasekoai.

Commenting on the judgment yesterday, Peta said it was a very important judgment in the development of case law relating to unlawful competition and fiduciary duties in Lesotho.

The Judge’s finding that fiduciary duties, in common law, don’t only bind directors but senior employees in key strategic positions, who are privy to critical and confidential information about a business, as argued by Loubser, was vitally important.

The point was made after Mugari and Tlali tried to argue that, unlike Chapatarongo, they were not directors of their employer.

Peta said the case had to be fought in the courts because the three respondents snubbed his efforts to settle the matter amicably out of court.

“As noted by the Judge, our lawyer Mr Fraser wrote ‘detailed, lengthy and comprehensive letters’ to the respondents asking them to desist from their illegal actions and giving them a chance to sit with us and find an amicable way forward, but all these letters were ignored,” Peta said.

Mugari was typically bombastic and arrogant, added Peta.

“He arrogantly told me in my face that the case would go nowhere.”

As stated in court papers, Mugari had been boasting to other staffers about how he had political allies and funders, and how they would use their power to thwart the applicants. He also boasted about what he claimed were his friendships to seven Judges.

“How then do you amicably negotiate anything out of court with a person so arrogant and confident about his influence…? asked Peta.

“Some of us have no high-level contacts and we can only seek recourse in the law. We are happy the law has protected us.”

Added Peta: “I am nevertheless dumbfounded by the unconscionable extents to which the very people we trusted, not only as colleagues but brothers, went about seeking riches at the expense of their legal obligations.

“Granted, there is nothing wrong with anyone seeking to purse wealth or any different goals in life, but why not do it properly and legally?

“Imagine how painful it is to learn that while we are paying people to work and advance the interests of our companies, they are instead busy conniving with staff to undermine and destroy the same companies responsible for their livelihoods for long periods while focusing on preparing a new competing venture.

“How more unconscionable can any human being get? Why not resign first, go out and start your new venture than use your employer’s resources to start a new competing venture?”

It is very notable that while Chapatarongo, Mugari and Tlali argued that preventing them from exercising their profession violated the constitution and public policy, the judge found that the three had sought to exercise their profession in a way that “is directly in conflict” with the very same constitution and public policy on which they now sought to rely.

– lestimes.com