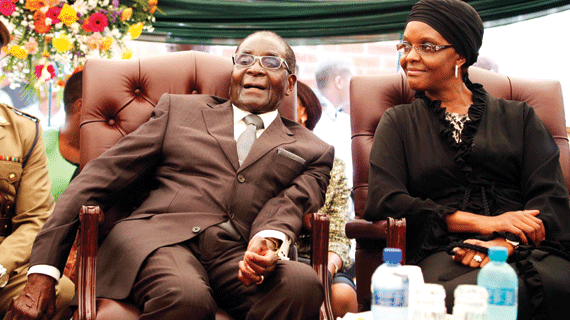

THE activation of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act in 2009, two years after it had been passed by Parliament, was inspired by President Robert Mugabe’s vindictiveness after his wife, Grace, lost a dispute over the supply of milk to Nestlé Zimbabwe, a senior researcher with the Research and Advocacy Unit, Derek Matyszak, has said.

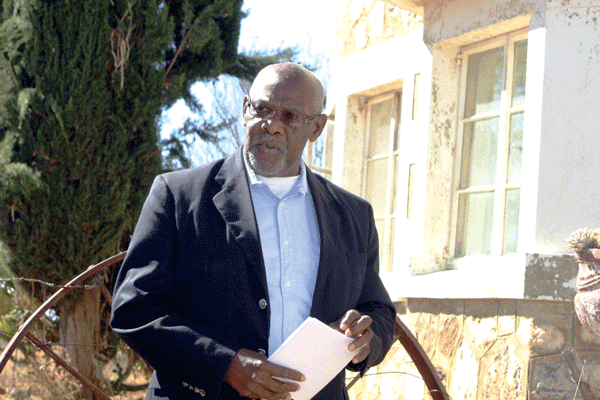

PHILLIP CHIDAVAENZI STAFF REPORTER

In a paper titled Madness and Indigenisation: A History of Insanity and in the Age of Lawlessness, Matyszak said the indigenisation policy has been abused to fulfill an individual’s parochial interests.

“The decision to activate the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act (Chapter 14:33), which had been passed by Parliament in December 2007, but had lain dormant until 2009, seemed to have been motivated by petty vindictiveness after president Mugabe’s wife lost a dispute over the supply of milk by her dairy business to foreign-owned Nestlé Zimbabwe,” he said.

“It (the policy) not only provided a means by which pressure could be brought to bear upon such recalcitrant companies, but also provided a seemingly inexhaustible well of rhetoric about sovereignty and fighting the capitalist imperialist monster in the form of foreign companies.”

Matyszak said the policy “fitted neatly” into the Zanu PF campaign in the run–up to the July 31 elections.

He said the inception of the policy was underlined by lawlessness as indigenous ownership of 51% of shareholding was a breach of the constitutional provision of freedom of association.

“If the Act was arguably ultra vires the Constitution, the Regulations also were ultra vires the enabling Act. The Act did not authorise the minister to make regulations compelling extant foreign companies in Zimbabwe to make changes to their share structure. Common sense indicates why this is so. Companies do not own the shares in the company — the members of the company do,” he said.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

He added it was almost impossible for a company to compel the transfer of a shareholder’s stock and there was no such provision in the Act.

“The Act also could not, as a general policy, seek to compel foreign shareholders to ‘dispose’ of shares so that 51% of a company’s equity was held by indigenous Zimbabweans because the problem of how to determine which shareholders are to relinquish the shares to make up the 51% is often intractable,” Matyszak added.