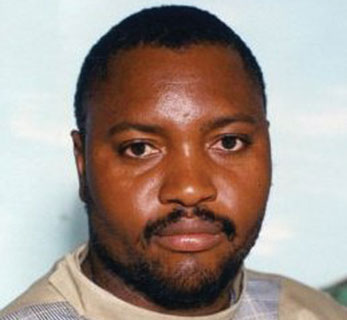

THE International Criminal Court (ICC) was established as an independent international institution for the purpose of prosecuting people who commit serious crimes such as genocide and war crimes, among others. MASOLA WA DABUDABU

More importantly, the ICC only complements national judiciary systems.

The ICC assumes full responsibility only where national judiciary systems negate their responsibilities to prosecute criminals.

It is a fitting tribute that some African Union member states were heavily involved in the creation of the ICC. In a continent bedevilled with internecine wars and wars of attrition, the ICC promised to check or moderate the excesses of the evil.

Although not a panacea, the ICC stands as an organ charged with exorcising the continent from its association with senseless wars and crimes against humanity.

In an unprecedented move, the African Union recently passed a resolution requesting the ICC not to take any incumbent African head of State for prosecution for crimes against humanity.

The summit also went as far as requesting that the pending case against President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya be postponed or else!

This resolution fell short of the radical demands of some member states who wanted a total withdrawal of the AU from membership of the ICC.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

According to reports from the AU summit in Ethiopia, the countries that were in favour of ditching the ICC were mainly from the Anglophone block.

Their quest was neutralised by member states from the Francophone block who argued in favour of an ongoing role for the ICC.

This clash in principles between the Anglophone and the Francophone countries in the AU is an indication of the cultures of impunity within one group and accountability in the other group.

It is not surprising at all that Kenya and Zimbabwe were among those who were strongly in favour of denying the ICC any form of role in Africa.

It is understandable that the two countries share a common antagonism towards the ICC. In both countries many people were needlessly killed.

The difference between what happened in the two countries is in the magnitude of the bloodshed.

Some Kenyans are being tried for their crimes while Zimbabwean criminals seem to have avoided the radar.

In Kenya, Kanu’s Kenyatta has been indicted to the ICC for suspected crimes against humanity.

This follows his alleged orchestration or participation in Kenya’s post-election violence of 2007.

Kenyatta’s aversion to the ICC seems to be guided by a guilty conscience.

The common factor driving Kenya and Zimbabwe’s leaders into a frenzy of antipathy towards the involvement of the ICC is guilt.

The guilty are afraid of being punished for shedding innocent blood. In Zimbabwe, Zanu PF’s Zvimba-born President Robert Mugabe has much more blood of the innocent on his hands.

Mugabe’s sense of extreme guilt has made him vilify the ICC as a vehicle for persecuting Africans.

Mugabe wants to convince his mutual admirers that the ICC is a racist tool that was developed to ensure the continued subjugation of Africans.

Mugabe is dying with guilt, but he does not want to atone for it in a court of law.

He knows that in the ’80s he unleashed his messengers of death to slaughter thousands of unarmed people in Matabeleland and parts of the Midlands.

This brutality became known as the Gukurahundi massacres.

Mugabe does not want to face the embarrassment of answering questions in front of a stern judge.

He has also been constantly blighted by election episodes that are devoid of compassion towards the electorate, especially those suspected of supporting the opposition.

It is easy to assume that during the 2007 Kenyan elections, Kanu found solace in reading from Mugabe’s election manual.

In Zimbabwe’s 2008 electoral farce, Mugabe actually took more drastic measures to outdo his previous record in electoral violence.

He cannot stomach the thoughts of being done a Slobodan Milosevic at The Hague.

He cannot fathom a situation where he is brought to account for each and every politically-motivated murder instigated at his behest or in his name.

Seeking the AU to server any ties with the ICC is Mugabe’s way of avoiding the prying eyes of justice.

It was a sad moment for Mugabe to see peers from the Francophone side of the AU coin saying “No” to pulling out of the ICC.

The compromise position that was begrudgingly adopted by the AU actually leaves the ordinary people with a lot of questions.

Why should someone commit crimes against humanity and not be prosecuted until they leave office?

What is so special about leaders who kill their people wantonly?

Is the AU not actually signing up to a cult of life president; leaders who would die in office than face the ICC for their crimes?

Is it why long-serving presidents like Mugabe nurse fears of living outside the protection of their presidential titles?

As Africans, we should feel ashamed that our leaders are unable to guarantee the well-being of their people.

If the leaders are to be taken as serious in their pledges to serve the people, then they should not have any issues in remaining signed up to the ICC.

After all the ICC is an organisation that seeks to prosecute ONLY those who commit crimes against helpless subjects.

African leaders should know that the leadership roles they assume are not licences to immunity for their excesses.

Masola wa Dabudabu is a social commentator