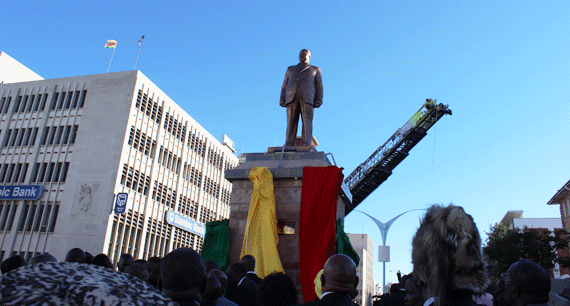

BULAWAYO and the whole country were treated to major events on December 22 2013 when President Robert Mugabe officially opened the Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo International Airport and thereafter unveiled the statue of Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo, simultaneously renaming its venue as JMN Nkomo Street to replace what was till then called “Main Street”.

The ceremonies brought welcome closure to two of the three irritants pertaining to Nkomo’s name, the remaining one being his dream institution Ekusileni Hospital that is still non-functional.

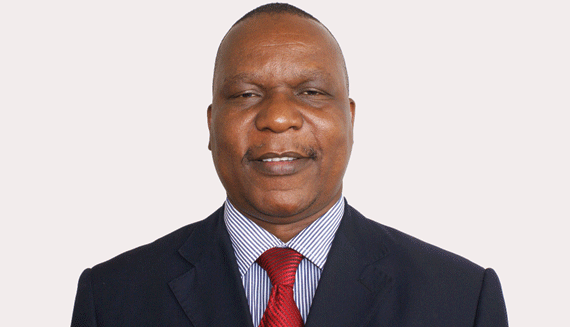

Zapu sent a delegation to the airport function led by its president Dumiso Dabengwa and also encouraged its supporters to turn up at the events honouring its founding president and enduring inspiration, Nkomo.

At the unveiling of the statue of Nkomo, Mugabe touched on the theme of unity because this was also Unity Day, marking the 26th celebration of the 1987 “Unity Accord” was signed upon the absorption of ZAPU into Zanu PF.

The president used that platform to bemoan the exit of Zapu the party resumed its independent existence in 2010. He issued a challenge to Zapu cadrés to “come back home” to Zanu PF and accused them of “infidelity” to Nkomo’s memory.

In his surprise call to Dabengwa and others who left the ruling party to get back together with their old comrades-in-arms, Mugabe was generally courteous and conciliatory.

However, the tone of the appeal suggests and has been picked up by commentators as a parental call to erring offspring to return to the family fold.

To the extent that Zapu and Zanu PF in the past formed alliances to deal with common challenges in spite of their differences, the two arms of the liberation movement accepted unity in diversity to achieve common goals.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Mugabe’s overt appeal, yet to be communicated formally to those addressed, raises a number of questions — more questions than answers. When Zapu members left Zanu PF in 2009, they did not become a rump of émigrés.

They were enthusiastically joined by many others who were active in the party prior to what could be called its “Babylonish Captivity” following its painful absorption into an unequal partnership with Zanu PF.

These people accepted that Nkomo did what he had to do to end harassment of his perceived followers in a protracted campaign to destroy Zapu that included massacres of civilian, but they did not follow their leader into the ruling party.

There are also many other people, particularly youth, who have either been brought up under the Zapu legend or see the unfulfilled agenda of the party as an answer to Zimbabwe’s current development and governance dilemmas.

These have nothing to do with Zanu PF and have never identified with it.

Therefore any approaches to Zapu have to be addressed to a complex membership.

It is also important to realise that those that made the revival of Zapu viable by pulling out of Zanu PF have no nostalgia for their long stay in the ruling party.

On the contrary, their experience and unfulfilled hopes and expectations are a good starting point whenever the subject of getting together is discussed.

Another useful starting point is that the revived Zapu is the only party that has a recent position on the “United Fronts” concept (based on the 1984 Congress) adopted at the end of 2012 and which contains parameters for working with others on set objectives.

In a guest column in the Southern Eye newspaper last week, Dumiso Dabengwa recalled how Zapu had been in the forefront of strategic alliances with Zanu at various phases of the struggle for independence.

In all these pre-independence alliances the two parties retained their separate identities and agreed frameworks within which to pursue common interests.

These 1972, 1975 and 1977 frameworks were in that order the Joint Military Council, Zimbabwe People’s Army (Zipa) and finally the Patriotic Front.

The 1987 “Unity Accord” departed from this tradition because Zanu PF was in a position to impose terms because it had a monopoly of State power and the instruments of coercion that had even made Nkomo flee the country for some time to evade threats to his person in the early 1980s.

The result is that Zanu PF even insisted on retaining its name and symbols as the insignia of the grouping that arose from the “Unity Accord”.

One sad outcome of the 1987 arrangement is that Nkomo was not only compelled by circumstances to accept absorption into the ruling party, but that in the sharing of State power he was made a second vice- president, playing second fiddle to first vice-president Simon Muzenda.

This was the unpalatable taste of a victor’s peace, a true “take it or leave it” arrangement that could only be tolerated while there was no alternative. The country, the region and the world have come a long way since then. There is much less necessity now of succumbing to lop-sided alliances and even much less justification for unconditional “coming back home” into any other party.

The significance of this changed environment has escaped some commentators who have used the recent harmonised elections as a yardstick to judge the significance of Zapu and its leaders.

Anyway, even if the elections were accepted as a valid yardstick one would have to take into account that our party fielded candidates in less than a quarter of constituencies for parliamentary seats and did not therefore at this stage of rebuilding its structures have illusions of forming a government on its own.

It is interesting that there is almost universal agreement that Nkomo was an unparalleled nationalist who subjected himself to the interests of Zimbabwe before his own.

This is what Mugabe drew attention to in his remarks at the unveiling of Nkomo’s statue in Bulawayo. It is a quality that should be emulated by all our leaders; being able to downplay personal egos and self-centered calculations when dealing with national issues.

There are many who value the humility and selflessness of others but are not willing to reciprocate, let alone take the lead. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that there are people in this country who value Nkomo’s humility because it paid them so handsomely, and they expect only humility and sacrifice from his followers.

If one looks at the enormity of Nkomo’s selfless contribution and what he endured in return, this could be put figuratively: “When he asked for sugar he got sand in his porridge instead”. The price he paid in 1977 does not need repeating over a quarter of a century later. The biggest positive result of the 1987 Accord is that it ushered in a period of calm by putting a stop to the official harassment of Zapu supporters. Mugabe should be given credit for his courage in describing the “Gukurahundi” genocide as “a moment of madness”.

There was hope that the 1987 Accord would therefore be followed by a process of apologising, peace-building and true reconciliation based on accountability for violation of individual freedoms and personal security as well as restitution for alienated properties.

The saddest example of a missed opportunity to provide a “peace dividend” is that in spite of efforts by leaders of Zapu inside the ruling Zanu PF there was no resolution to the return of properties summarily grabbed from a holding company, Nitram (Pvt) Ltd, combining Zapu properties and properties bought from contributions by Zipra cadrés largely from their demobilization payments.

Thirty years after these properties were grabbed they have yet to be returned. Consequently, many comrades who had expected livelihoods from them have either died in poverty or are living a miserable existence in their old age.

Many families would also have had the benefit of this far-sighted planning of Nkomo who believed ardently in hard work and self-reliance.

The case of Zapu and Zipra records confiscated in the early 1980s is another issue that could have been settled easily because these were important for chronicling the prosecution and evolution of the struggle for independence and the politics of our liberation movement as a whole.

The country is poorer in its collective memory for absence of such documentary records.

Needless to say, there may be some who wanted to expunge (as evidenced in distorted history by some writers) or downplay Zapu’s contribution to Zimbabwe’s liberation, but our share of this country’s history is sufficiently etched in folk memory.

This is enough reason for maintaining a distinct identity because immediate gratification is not part of our make-up.

The conferment of national hero status should not be an issue for settling scores among those who made significant contributions to the liberation of Zimbabwe.

In the event that there is no consensus about the record and significance of particular individuals, it ought to be the duty of respective parties to make an objective case for recognition.

This sounds obvious until you go through the list of Zapu and Zipra heroes who missed out, even from retroactive conferment of due recognition.

In the aftermath of the 1987 Accord there should have been no cases where distinguished veterans were denied State recognition just because they joined those who pulled out of Zanu PF.

Apart from being aimed at denigrating outstanding Zapu fighters and veteran politicians on the basis of their current status, the net result of this practice has been to highlight that the ruling party belongs to the original owners of its name.

Indeed there are numerous illustrations of this more and more often as the generations of war veterans pass on.

We shall continue to celebrate the sterling contributions of our gallant fighters and not bargain for their status.

As they would say in parts of Matabeleland South, Kakho ozimuka ngesitshwala sokugalila”, (No-one can thrive by hanging around for the food of neighbours during their meals”.

The Unity Accord has failed because of repeated reference to the need to revisit its terms yet in over 20 years of its existence there has been no such review and necessary amendment. Any Zapu discussion with Zanu therefore would have to be based on the United Front concept, ie on a clean slate. Once beaten twice shy. Issued by the Zapu presidency