RECENTLY, a close friend of mine attended an international women’s conference in Malaysia and she frequently shared some of the speeches and remarks online — being made by various leaders of women’s movements across the globe.

Agreeing to disagree with Delta Milayo Ndou [email protected]

In most of the remarks she shared, I kept stumbling across the suggestion that women’s rights activists must not speak from their “positions of privilege”, but must remain relevant and in touch with “the ordinary woman” that they purport to represent.

It is an admonition I have heard in other forums, where activists advancing various causes are continually reminded that they must return to “the grassroots” and avoid strategising, planning and operating from the ivory tower of privilege.

But who is this ordinary woman? While I concede that women are not a homogenous entity and that there are various markers of difference that can be used to classify us according to the commonality (or lack thereof) of our lived experiences, I have a hard time pinning down what is considered as “ordinary”.

When we are rebuked for speaking on behalf of the “ordinary woman” whose realities and struggles we might not have any experience of — are we being indirectly told that we are not qualified to care about the plight of those whose life stories are at variance with our own?

When we are told that we are “privileged” — are we being told that our presumed privilege insulates us from being empathetic?

Who is this ordinary woman and who is to say that at various stages in my life and in different seasons of my journey I have not been that “ordinary” woman or walked in her shoes?

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

I think when people speak of privilege and scold us for thinking we know what’s best for the “ordinary” woman they are forgetting that for so many of us “privilege” is a by-product of struggle, a reward for sacrifices made and the attainment of what we once aspired to become.

Some of us were not born into privilege – we were born into the average Zimbabwean family and raised with the tag of “ordinary” as a default identity.

It is unfair, I think, to then consider us products of privilege when the vast majority of us are products of guts, hard work, struggle, sacrifice, determination, ambition and mostly tears.

We are the products of the tears of our mothers and their mothers’ mothers who raised us to claim a space of our own in a world that gives one nothing for free.

So when we speak of “ordinary” women, we speak of ourselves, of the women or young girls we once were and we speak of the women whom we modelled ourselves after — we speak of our sisters, our aunts, our cousins, our neighbours, our grandmothers and we speak of those whose lives impacted on our own.

We speak of our ordinariness in a world that only recognises our recently-acquired cloaks of privilege and uses those cloaks to delegitimise our voice because apparently we are “too educated” to know what it’s like to be illiterate; we are “too refined” to know what it’s like to be impoverished; we are “too travelled” to know what it’s like to live your entire life within the circumference of a village and we are “too driven” to know what it is like to be desperate.

I think our differences are more superficial than fundamental. I think that our commonalities often outweigh our social, class, or status-related stratification.

Perhaps to speak for myself (as is often safe and wise to do) — I am an ordinary woman who has a few modest accomplishments.

These accomplishments are just an adornment that I can easily be divested of, but what lies beneath — what is integral in me — is that I was born in Beitbridge (at the periphery of the map) and I was born into the Venda ethnic group (a minority) and I was born female (fated to belong at the margins of a patriarchal society if I hadn’t fought my way into the mainstream).

I can speak of village life with as much authority as I can speak of life at one of the top 15 universities in the United Kingdom. I was born into the former and later in life, I had the “privilege” of experiencing the latter.

My point is, activism is a matter of caring especially when you’re not expected to care and when you’re under no obligation to care.

Beneath the superficial trappings of whatever we’ve managed to attain in terms of status, wealth, education, career advancement or whatever else we have succeeded at — I think we are all “ordinary” people. But that’s just me. We can always agree to disagree.

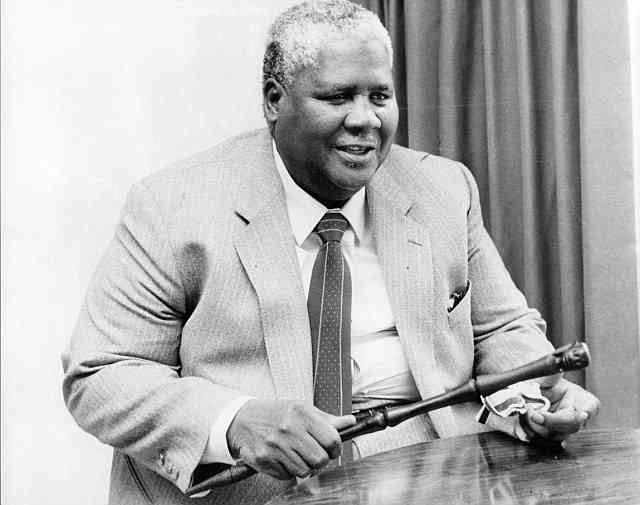

Delta Milayo Ndou is a journalist, writer, activist and blogger