QUESTIONS are often asked around constructive dismissal — what is it? How can I claim constructive dismissal?

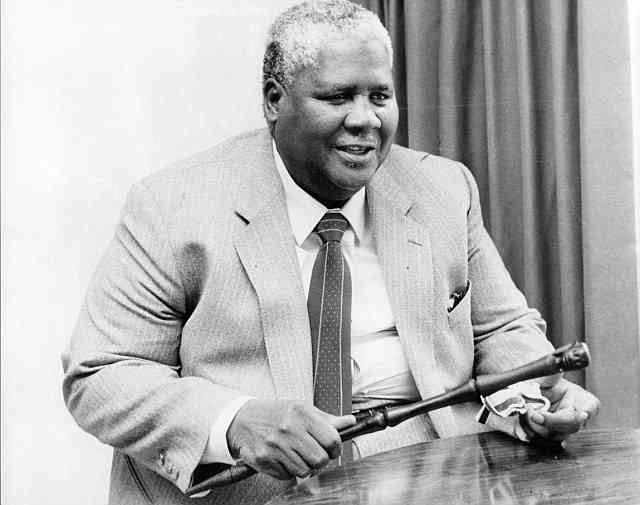

-ELIAH ZVIMBA And employers ask the question “the employee has resigned and is claiming a constructive dismissal, what do we do?” Firstly, let us understand what it is.

Constructive dismissal occurs where an employee terminates his employment contract in response to his employer’s treatment. Although there has been no actual dismissal, treatment is sufficiently bad that the employee is entitled to regard themselves as having been dismissed.

Taking reference to our own Labour Act, Chapter 28:01, Section 12B: “An employee is deemed to have been unfairly dismissed if the employee terminated the contract of employment with or without notice because the employer deliberately made continued employment intolerable for the employee.”

From the perspective of common law, this looks like a resignation or a termination of contract by the employee, but it is in fact, a dismissal by the employer.

In Pretoria Society for the Care of the Retarded v Loots (1997) the court referred to Jooste v Transnet Ltd t/a SA Airways (1995) stating that the first test was whether, when resigning, there was no other motive for the resignation in other words, the employee would have continued the employment relationship indefinitely had it not been for the employer’s unacceptable conduct.

The court further stated, “when an employee resigns or terminates the contract as a result of constructive dismissal, such employee is in fact, indicating that the situation has become so unbearable that the employee cannot fulfill what is the employee’s most important function . . . that is to work. The employee is insisting that he could have carried on working indefinitely had the unbearable situation not been created.”

When any employee resigns and claims constructive dismissal, they are in fact, stating, that under the intolerable situation created by the employer, they can no longer continue to work, and has construed that the employer’s behavior amounts to a repudiation of the employment contract.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In most cases, women are more vulnerable to sexual harassment where they just suffer silently and decide just to leave the company. Some employers usually verbally attach the employee or assign unrealistic sales targets and heap the problem to the employee. In view of the employer’s repudiation, the employee terminates the contract.

In bringing such a dispute, it is for the employee to prove that the employer was responsible for introducing the intolerable condition and to prove that there was no other way of resolving the issue except resignation.

It is not for the employer to prove that he did not introduce any intolerable condition.

In Jooste v Transnet Ltd t/a South African Airways, it was held that, “for such a dispute to succeed, the employee must prove that he or she had not intended to terminate the employment relationship, but was left with no option, but to do so because of the employer’s unacceptable and intolerable behaviour”.

Unfair disciplinary action taken by the employer could constitute a breach of contract and may amount to constructive dismissal.

However, resignation to avoid a disciplinary enquiry does not amount to constructive dismissal.

The resignation of an employee in the face of a disciplinary hearing and resigning in order to avoid the disciplinary hearing would not necessarily constitute constructive dismissal.

It may well do so if the employee was threatened to resign or face a disciplinary hearing where they will be dismissed anyway.

That sort of thing might justify a dispute of constructive dismissal. The employer is still entitled to proceed with the disciplinary hearing in absentia.

In Watt v Honeydew Dairies (Pty) Ltd the commission emphasised the difficulties faced by any employee who contemplates bringing a claim of constructive dismissal: “It is submitted that an employee bears a considerable risk in the case of constructive dismissal.”

One of the first requirements of a constructive dismissal is that the employee must resign. This in turn means that if such an employee is unable to show the requisite conditions that render continued employment intolerable, then that resignation remains valid (as resignation not as constructive dismissal).

Resignation need not be the employee’s only option, but should be the only reasonable option for a claim of constructive dismissal to succeed.

It has been found that acceptance by any employee of the employer’s repudiation of material terms of the contract amounted to constructive dismissal.

This would include suspension of an employee without pay after the employer experience financial difficulties.

In other matters sexual harassment, resulting the employee’s resignation, may also constitute constructive dismissal.

In Van Der Riet v Leisurenet Ltd t/a Health&Racquet Club, the employee resigned after being effectively demoted as a result of a restructuring exercise.

The employer’s failure to consult with the employee on the possibility of the demotion was considered unfair, and provided a sufficient basis for a claim of constructive dismissal.

A demotion in another case also justifies the claim of constructive dismissal.

From the above, it will be noted that constructive dismissal is very complicated, and there are no hard and fast rules.

Each case must be judged on its merits, and whilst there is an onus of risk placed on the employee in having to prove the dismissal, employers must also be aware of their behavior and the way in which they handle employees.