THE BOAT is small, just big enough for six passengers and our driver, who doubles as our guide. We’re on a lake in the vast, remote Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve in south-eastern Zimbabwe.

Mary Ann ANDERSON Own Correspondent

Across the hills, the sun is veiled in the last light of day. Darkness will come soon.

All around us, hippos splash, snort and grunt and generally cause an alarming stir in my heart. Two of my three travelling companions are at the front of the boat, in the appetiser seats. If anything should happen, if we bump into a hippo or a log or, whatever else lies waiting in the lake, they’ll be shrimp cocktail.

I’m at the back of the pontoon, in the dessert seat, if you will, listening to the hippos and the other myriad sounds of an African nightfall.

In a few moments, elephants come crashing through the bush to the lakeside for their last drink of the day, their stomachs rumbling low like distant thunder. There’s no other sound like it on Earth. Against the backdrop of the sun, a gaggle of Egyptian geese serenades the orchestra of elephants and hippos.

Tengwe Siambwanda, our guide, has what one of my companions has termed the “most ridiculous eyes” and can see everything. By now, it’s heavy dusk and I never would have spotted the black rhino standing at the water’s edge if Tengwe hadn’t pointed him out.

At first, the ungulate seems surprised by the boat, but then he becomes agitated. Here’s what an agitated rhino does: He kicks up a dust storm, stomps his hooves like a two-year-old who hasn’t gotten his way, knocks over a couple of trees, and then mock-charges. For a moment, I wonder whether he’ll leap into the water and sink the boat.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

If he does, I’ll be faced with the split-second decision of whether to face a single grumpy rhino or a bevy of hippopotami.

Thankfully, I don’t have to make that choice. With little light left except that of a sliver of moon and more stars than anyone could possibly count, Tengwe quietly backs up the pontoon, away from the natural circus of rhino, hippos and elephants and carefully motors back to the dock, bringing a grand end to our boat safari.

I’m on a voyage to Africa, my ninth to this most wondrous continent, but my first to Zimbabwe. It’s a women-only trip and we’re staying at Singita Pamushana Lodge, about a two-hour bumpity-bump twin-engine plane ride from Johannesburg. At the beginning of the customised group tour, the other women and I don’t know one another well, but by the end, we’re friends who have shared some truly special moments in a place so far from home.

There are usually two themes that run through a women-only trip. The first is forgetting husbands, children, parents, pets, problems and whatever else back home and having fun. The other is that on a trip to an uncertain area, there’s safety in numbers.

As a group, the four of us are practically fearless, although many people advised against going to Zimbabwe because of the Robert Mugabe regime.

“It’s dangerous,” preached one gentleman friend, a big game hunter who had visited many years before. “It’s not safe. Women don’t need to be going there alone.”

“Don’t go,” warned another male friend, who had worked with the State Department. “Mugabe is crazy and everybody is poor and desperate.” But wanderlust prevailed, as it always does for travel junkies and we were off to Africa.

As we putt-putt across the sky from Johannesburg to Buffalo Range airstrip near Singita, I strike up a conversation with my seatmate, a soft-spoken young woman from Harare the capital. I ask her whether we need to be afraid.

“Zimbabweans are very passive,” she replies, quelling any uneasiness I may have felt. “Despite what you might read, we don’t like trouble.”

When we land at the airstrip, I half-expect our group to be interrogated, hissed at or called stupid Americans. But no, the customs officer is delightful, her face full of kindness and when I make a corny joke, she laughs with me, heartily and easily. She’s my introduction to Zimbabwe, and I know that everything will be just fine.

On the almost hour-long drive to Singita from the airstrip, we pass villages, herds of cattle and goats, and miles of dusty woodland honeycombed with acacias. My eyes search for an errant lion, perhaps a leopard, but any critters would blend into the warm, rusty hues of the landscape.

In the road ahead of us is a security checkpoint and for the first time, I’m a little nervous. But all my fears are cast aside as the armed police scowl a bit, but then smile broadly at our vanload of ladies. Obviously, we don’t look threatening and with a wave and another smile, we’re on our way.

Within moments of our arrival inside the boundaries of Singita, in the heart of the Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve, we pass very close to several giraffes. They stare at us blankly, a sort of “duh” look on their faces, before lankily bounding off into the bush. We’re so close that I can see their long, curled eyelashes shadowing the brownest, sweetest eyes.

There are only eight of us at the lodge: Our group of four women, a couple from Australia named Dee and Peter and John and Karen, a couple from Florida who have already been at Singita for a week. Amused that a group of ladies are traveling on their own, the two couples quickly become our pals.

The Aussies are friendly and Peter, the husband, a big bear of a man, immediately takes us under his wing, appointing himself our caretaker. He watches our every move, always the gentleman, but apparently ready to assume his role of The Man should one of us damsels get into distress.

Jason and Emily, managers of the lodge, welcome us and explain that the 150 000-acre Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve, which abuts Gonarezhou National Park on the border with Mozambique, was established by conservationists in 1994, primarily to protect wildlife from poachers. The lodge, says Jason, is the “ecotourism arm” of the reserve, and the proceeds from guests go to wildlife conservation and community outreach.

On our first game drive, I call shotgun and climb into the front seat of the Land Rover. As we drive over the next few days, we learn that the geography of the reserve runs the gamut from acacia woodlands to plains and that the animals are as stunning as anywhere in Africa.

I even manage to spot a sable, an exquisite creature that I’ve never seen before, its black fur gleaming in the hot African sun.

The requisite Big Five — Cape buffaloes, rhinos, elephants, lions and leopards — are all on the reserve. So are a billion birds. Rollers, weavers, hornbills, owls and egrets flit all around, their jewel colors giving away their hiding places in the trees. I can’t get enough of the lilac-breasted rollers, their pastel feathers as vivid as an Impressionist painting.

As we explore the reserve, I etch in my mind forever the colours and textures and especially the sounds of Zimbabwe, where it’s quiet but never really quiet. The wind is always whispering, and the ground is always trembling beneath the hoofbeats and the wing tracks of the most amazing wildlife and bird life.

Perhaps one of my companions says it best as we watch giraffes drink from a watering hole: “You feel as if you’re underneath mother earth.”

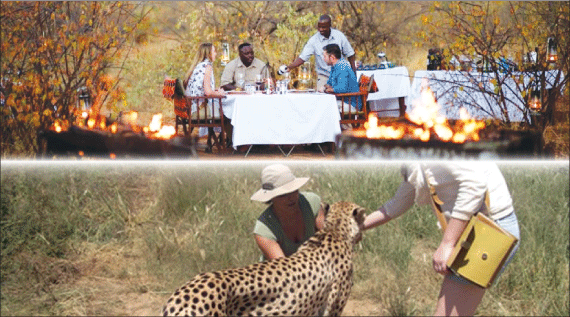

On one evening of our three-night stay, Jason and Emily host a wonderful wine dinner, pairing bold South African reds and whites with local game. As a semi-vegetarian, I’m glad that I don’t have to face the choice of eating what I’ve just photographed.

The next day, Tengwe takes us to the Kambako Living Museum of Bushcraft just beyond the borders of the reserve. It’s a small Shangaan village, the Shangaan being one of 12 or so cultural tribes in Zimbabwe.

Together the four of us watch and listen as Julius, patriarch of the village, crouches low to the ground to make fire. “We are trying to teach others about our old ancestral ways,” he says in excellent English, spinning two sticks together until they spark into flame. “We are trying to keep the old traditions alive.”

Guiding us around the village, Julius and some of the other young men teach us how to forge metal spearheads while the wives and daughters weave baskets from grass and cook on open fires.

“Men’s work is men’s work and women’s work is women’s work,” Julius says matter-of-factly. Agree or not, his old-fashioned views draw no argument from us. You don’t squabble with a man holding a spear.

When Julius divines for water using a tree branch as a rod, I don’t believe that it can really be done and have to try it for myself. As I grab the branch and hold it as Julius instructs, something akin to a mystical force swings the rod downward. I’ve actually struck water, and I’m practically bouncing with joy.

“There,” Julius says, laughing at my excitement. “Dig down, and you’ll find water.”

After watching a boisterous, colorful Shangaan dance, we drive back to the lodge, where later we feast at an outdoor dinner beneath the shadows of an immense baobab tree, our eyes always trained to the bush to keep a watch out for hungry lions.

After an early morning game drive the next day, we visit another village to learn about community projects that focus on malnutrition, feeding programmes, education and malaria prevention.

Shepherd Mawire, the community development coordinator for Malilangwe, explains that 19 000 children, from six months to five years of age, are fed daily by the largest project in Pamushana. He next takes us to a school a few miles away. It’s blazing hot, and there’s no air conditioning, only open windows and doors. But no one complains. You can’t miss what you’ve never had.

“Most students want to be teachers, nurses and drivers, because that’s what they see,” Mawire tells us as a group of schoolchildren sing and dance for our group. “Education is a high priority.”

On our last game drive, we come upon a herd of elephants in a deeply forested corner of the reserve. After watching them for a while, we begin to drive away, when one breaks away and runs after us.

Finally, the big bull gives up the chase and trumpets at full volume, a soulfully soothing sound, that of the grandest beast of Africa. I thought I could stay there forever watching him. As we begin our long sojourn back to the States, the consensus among us is that everyone who warned against the dangers of Zimbabwe was completely wrong.

Not once have we felt threatened in any way. I’ve been to Africa several times, as a journalist, a tourist and a women’s tour group leader, and I found Zimbabweans to be among the warmest, kindest people I’ve ever met.

Back at Buffalo Range airstrip, our passports stamped with exit visas, I think of one of Hemingway’s most inspiring quotes: “I never knew of a morning in Africa when I woke up that I was not happy.”

And in the heat of the day, we women spring together for one last group hug on the African soil. I breathe in Zimbabwe one last time, deeply, and then climb aboard the tiny plane for the long journey home.

— Washington Post