IN just over a week Zimbabweans will be celebrating their country’s 34th independence anniversary.

Many will be reflecting on the trials and tribulations of the war of liberation. They will also look at their post-independence fortunes or misfortunes. They will question whether the attainment of independence has lived up to expectations.

Nostalgia will obviously set in as people recall how they were invited to take part in the struggle. The affected people will still remember the aggressive and coercive nature of the invitations extended to them to join the struggle.

They will not have forgotten that forceful abduction of able-bodied men and women, including schoolchildren, was the preferred recruitment method.

In July 1973 almost 300 students from St Albert’s Mission in Centenary experienced the trauma of being temporarily abducted. Manama Mission and Thekwane Secondary School in Matabelaland South suffered wholesale abductions of their student populations.

The survivors from these abductions will be taking stock of what the country has done for them after they gave away their innocence to the brutalities of an armed conflict.

Many more were compelled by the smooth-talking recruitment officers. They did not mince their words as they reminded the people about the evil whites. People were given a rude awakening on the repulsive state of the township hovels they lived in.

The structures in Makokoba in Bulawayo, Rimuka in Gatooma (Kadoma) and Harare Township in Salisbury were criticised and likened to underground burrows for rodents.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Potential recruits were enthused by the prospects of suburban mansions. They naturally obliged by volunteering to be the cannon fodder. As they fought, the people could not stop imagining the day they would finally settle in some spacious bungalow somewhere in Kumalo or in Mount Pleasant.

Others were made aware that they were labouring hard as housemaids or garden-boys for the opulent white baas under sub-human conditions. General farm hands at baas’ farm could not ignore the promises of owning the farms.

The recruiters organised weapons and instructors from communist nations to teach the recruits how to fight a war. The mountains, the valleys, the ravines and the plains teamed with armed men who had been indoctrinated with blind obedience and unwavering servility.

The fighters embraced the spirit of supreme sacrifice and indeed many sacrificed their lives.

The road to freedom was thorny and torturous. Some died, others were physically damaged and disfigured and many more were destroyed emotionally.

Civilians in the conflict got the worst end of the deal as women and girls were forced into sexual relationships with the armed. On the other hand, civilian men and boys were humiliated in the game of domination by those who were armed.

Today, 34 years after the war of liberation ushered in independence, there is not much to show for it. The same structures and systems that were criticised as subhuman still stand defiantly as if to mock the ideals of the struggle. The hovels that were so despised still stand strong and continue to poke fun at those who joined the struggle on account of the housing disparity.

Here and there mansions, few and far apart, seem to stand their ground to make a statement on life’s inequalities.

Those who invited the people to fight for freedom are still around. They are no longer on the same level with the ordinary people. They are untouchable and unreachable. They are the new “whites” who are blessed with a touch of more melanin and more money.

They behave in exactly the same way the white baas used to. They are drunk with arrogance and they are drowning in ill-gotten opulence. They look upon the ordinary people with indignation.

The barren lands in the former Tribal Trust Lands are still populated by poor peasants. The winds of change have only deposited dust and more poverty on the areas. The farms that were liberated are for the pleasure of the very select few. The new management on the farms consists of neo-whites with a shade of darker skin.

The working conditions for the farm labourers remain unchanged. The productivity levels have been maintained at subsistence levels.

Those who participated in the liberation struggle have been left with a “used condom” feeling. They feel that they were used by the new brand of masters only to be discarded in the sanitary bin after. No one takes a second look at a used condom and no-one reuses a used condom.

In the wake of all this class disparity, inequality and poverty, another struggle of liberation may be in order. Zimbabweans have been robbed of their dignity by the new whites. The people have to reclaim their dignity by freeing themselves from the “used condom” insult hovering over their heads like a halo.

As the nation celebrates another meaningless milestone, the people crave for matunda ya uhuru — the fruits of independence.

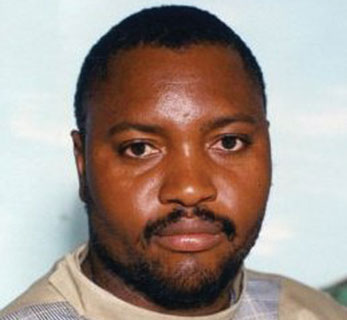

Masola waDabudabu is a social commentator