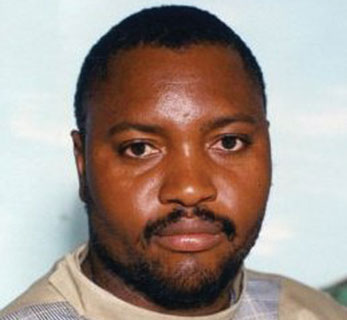

I RECENTLY made inconspicuous forays into motherland and I was greeted by a country laid to irrecoverable desolation. Masola wa Dabudabu

I traversed my beloved Plumtree and I was greeted by dehumanising eyesores which were camouflaged by some false optimism that radiates from the people’s faces. There was some North-Korean type of State-designed and State-prescribed contentment.

The truth started coming only after the flow of alcoholic beverages purchased the confidence of some of the influential villagers.

They spoke of fear, they mentioned desperation, they hinted on exasperation and they decried the confusion within.

They drunkenly spoke about a dark force that has overwhelmed their flesh and sapped the juices from their souls.

When I sought clarification they said they were only speaking in allegories.

I left Plumtree a disappointed man for in my own eyes I had witnessed the stagnant, if not negative growth staring back at me.

I would have gone to the Plumtree/Ramakgwebana Border post to see the border jumpers, the smugglers, the stock-pile of cars imported via Walvis Bay and the town’s conmen and crooks at work. Instead, I chose to hike a lift from an injiva’s car to Tsholotsho.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The injiva, whom we shall call Oscar, said he was lying low after he was nearly arrested during a botched attempt to rob a bank in Johannesburg. He said he planned to con people for anything from money to movable property of any sort including cars.

He said he would use his contacts at Zimra to dispossess absent car importers of their cars.

On the dusty journey to Tsholotsho, poverty, hunger and sickness kept on replaying in my eyes as if someone was playing a vinyl record with a scratch. Tsholotsho centre did not look any better. There was nothing extraordinary about its economic state. The whole place was dominated by bare-footed villagers who seemed to endure the piping hot surface of the tarred main road on their mission to soothe their throats with alcohol at one of the many liquor stores.

I was fortunate to bump into the “district chairman”. He spoke of the desecrated graves of the district’s illustrious sons and daughters. He alluded to some unmarked mass graves for those massacred during what he termed “the years of internal strife”. He said the outlook was not bright at all.

According to the chairman, the country would be embroiled in a war of resources.

His view was that the proceeds from the tusks of culled or killed elephants were benefiting some royal district in the far north instead of contributing towards the welfare of people in areas where the elephants were culled or killed.

The district chairman spoke about animals dying from drinking poisoned water. He whispered that villagers were going to pay with their flesh for all the dead elephants.

The district chairman said the cyanide war and the search for six foreign tourists who were allegedly abducted by dissident elements in July 1982, had operational similarities. The people were feeling the heat from the reprisals.

The district chairman’s prognostication on the future was chilling. I had to bid him farewell. Lupane was my next destination and it did not fail to disappoint.

I looked for my erstwhile acquaintance, the legendary Duke of Lupane. He was not there; actually he is no more there. I was told that he had succumbed to the illness of irresponsible sexual exploits like most men of his sexual predation. I honoured him with an untimed minute of silence after a man known as Mukoma Hirariyo (probably Hilario) offered his services as a tour de guide.

Hirariyo showed me what he termed the pride of Lupane. He hinted that it was still under construction. He bragged that once completed, Lupane State University would rival world-known universities.

He dampened my excitement when he whispered that he knew of someone who could arrange a genuine fake degree qualification (take-away degree) from the institute. I paid Hirariyo his $5 “consultation fee” before heading for Binga district.

Binga was a personification of desolation, strife, despondency and misery. I saw the state of disrepair. The sandy soils had no sign of life. Siyamande, a devoted party operative livened up the place. He asked me if I had any links to the ruling party. When I said I was an apolitical person, he sighed in relief.

He said whatever I visualised as far as my eyes could see defined Binga district. He lamented the lack of political zeal to uplift the quality of life in the district.

I looked and with my eyes I saw criminal neglect by a government that prides itself for being people oriented. Siyamande said the state of Binga district was a living testimony of the effects of punitive sanctions imposed on the district.

Goodbye Binga! My brief sojourn in those districts revealed that most Zimbabweans falsely portray themselves as a happy people yet they live in bondage.

Indeed Zimbabwe is riding the crest to self-destruction. The nation lays in waste just as its people are wasting away in flesh. The future is grim, the prospects for good health are dim and chances of universal prosperity are slim and trim. Surely the people of the south deserve a better Zimbabwe experience! Masola wa Dabudabu is a social commentator