Nowadays the media is abuzz with talk about revival of Bulawayo industries. The question is – when did Bulawayo industries die?

Ian Ndlovu

The necessity of revival implies that they are dead or moribund? A similar question is — if some of Bulawayo’s industries are no longer alive, what factors explain their apparent death?

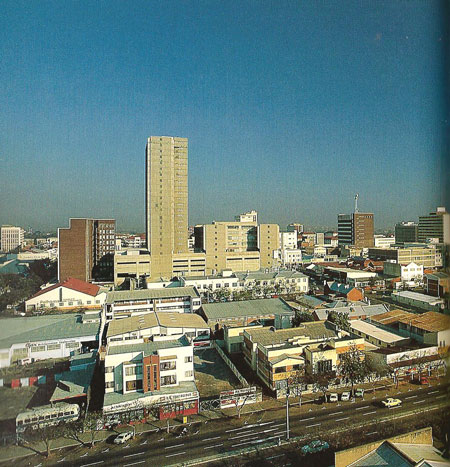

The point that Bulawayo was once the industrial hub of Zimbabwe cannot be debated because it is documented in many studies as an empirical fact.

A survey of the industrial location of Belmont and closer to the inner city, reveals that once roaring factories are now shells of their former selves.

It is a sorry sight when one visits what were once vibrant industries along Plumtree Road. Some of the big factories have been churches and small-scale homelike industries that do not use sophisticated or state-of-the-art technologies.

The question is — why is that when other cities were urbanising to become sprawling urban centres, Bulawayo has consistently not experienced residential growth? A careful examination of the site and situation of Bulawayo reveals that the city is located in the semi-arid part of the country.

This implies that Bulawayo experiences or is bound to experience acute shortage of water.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Water is a basic input in the production processes of most industries. It is nearly impossible to imagine any company experiencing meaningful future growth without a steady and consistent supply of water. To say that water is a problem in Bulawayo is an understatement, water is actually a matter of city life or city death in Bulawayo.

Any microeconomic plan which is meant to boost operations of Bulawayo industries which excludes a permanent solution to the perennial shortage of water has high chances of being doomed.

There was a time when companies were relocating from Bulawayo to Harare and other parts of the country.

Migration of firms just like migration of people is occasioned by economic, political, geographical (physical environment, climate, and so on) and sociological imperatives.

The emigration of some companies from Bulawayo to Harare was a characteristic of the behaviour of firms in many developing countries that follow a unitary or centralised system of government. Naturally firms would find it easier to operate in a place which is a seat of political and economic power such as the capital city.

It is the belief of this article that decentralisation and speeding up of State decision-making would go a long way in stemming the sub-economic intercity migration of companies.

Decentralisation and catalysing of government decision making may involve for instance embracing the recent phenomenon of electronic-government or e-government.

E-government means substituting antiquated and archaic paper based government systems with electronic information processing and communication channels.

Be that as it may, it is important to observe that some of the companies that relocated from Bulawayo to Harare eventually relocated to other countries or closed shop during the economic meltdown of the late 2000’s prior to the current decade. The answer to this phenomenon is stabilisation of the economy as a whole.

An unstable economy influences companies which are components of that system to be unstable as well. This implies that one of the major priorities of the new government is to ensure a stable economic environment underpinned by a strong incentive system to reward companies or firms that operate profitably and sustainably.

Since Bulawayo industries started declining in real terms during the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme it is important that various forms of government mobilise funding and technical support to capacity-build Bulawayo industries.

A strong incentive system must be put in place to reward companies that manage to break even and make a profit within specific time frames.

These incentives may be in the form of partial or total relaxation of import duty for such firms if they use imported inputs, tax holidays, subsidies, grants, soft loans, technical support in the form of training and retraining at concessionary rates.

The establishment or gazetting of certain areas as protected or special industrial zones with attendant benefits may also go a long way in providing economic relief to distressed companies.

A key factor which needs deeper investigation which may explain the collapse of industries in Bulawayo is the impact of globalisation of production and distribution of goods and services.

The question which we need to ask ourselves is — do we really need to second-guess China in producing goods that they produce well having achieved economies of size, technology, production, marketing and distribution worldwide? The clear answer is – since Zimbabwe is a small country, we cannot afford to duplicate what a powerful and fast developing economy like China is producing efficiently.

If in the past Bulawayo was dominated by clothing and other related industries, innovation and creativity imply that all affected stakeholders need to identify the remaining and new industrial strengths of Bulawayo and maximise on those instead of trying to revive those industries that the Chinese are operating better and at lower costs than us.

Bulawayo may for instance focus on promoting tourism, light manufacturing, assembly and light assembly of products instead of attempting to produce commodities which are produced elsewhere using superior technology and cheap labour.

In the final analysis, industries and the economy of Bulawayo may be sustainably revived if and only if all key stakeholders work as one.

This means that though the Bulawayo council and central government may speak different political languages at times due to divergent ideologies, the two sets of leaders need to find or create bridges of communication to ensure a steady and positive dialogue on Bulawayo specific problems and national issues that impinge on the development of Bulawayo as an economic, social and political zone.

Ian Ndlovu is an economics lecturer at the National University of Science and Technology. His research interests cover business, development, economic and e-commerce issues. He writes in his personal capacity.