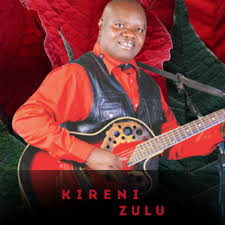

KING of Marabi music Kireni Zulu, alongside Jenaguru Music Festival founder Clive Malunga, the National Arts Council of Zimbabwe, the Zimbabwe Union of Musicians and the Arterial Network, has in recent years intensified advocacy for the improved welfare of creative industry practitioners.

Their campaigns highlight a persistent gap between artistic success and long-term security, urging creatives to treat their careers as structured enterprises that require planning, protection and discipline beyond performance and applause.

This stance was clearly illustrated at the funeral of Nicholas Madzibaba Zakaria, a musician remembered for living with purpose and restraint.

During tributes, Zulu announced plans to establish an endowment fund to support musicians’ widows and living legends.

To advance this vision, he recorded a collaborative album featuring nearly 30 artiste, turning loss into action and remembrance into legacy building.

The initiative reframed funerals not as moments of regret, but as opportunities to institutionalise dignity, continuity and collective responsibility within the arts sector.

Zulu, celebrated for classics such as Mhembwe Ine Bhachi, Samson naDherira, Mazai Adhimba and Jongwe, later told NewsDay Life & Style that deprivation should never be accepted as an explanation for financial collapse.

He called on stakeholders to provide financial and material backing that preserve musical heritage and honour its pioneers.

- In the groove: Celebrating the life of James Chimombe (1951-1990)

- In the groove: Celebrating the life of James Chimombe (1951-1990)

- Building Narratives: Whispers of Soil: A clarion call to preserve African pride

- Mbuya Stella Chiweshe, Zim’s music ambassador: Malunga

Keep Reading

Central to his argument is the belief that artistes must resist degradation and refuse to surrender their creative legacies to hardship.

His initiatives, including anti-drug campaigns, music legends programmes and widows’ support projects, position discipline and collective care as professional responsibilities.

From Johannesburg to Harare, however, evidence shows that fame without financial discipline remains fragile.

South African television and music histories reveal repeated patterns of careers unravelling once contracts dry up, income stops or personal discipline weakens.

Former stars such as Marlon Rives, Roderick Jafta and Sofili Chava demonstrate how unemployment, poor planning and limited networks can lead to homelessness.

Their experiences reinforce Zulu’s warning that deprivation should not be romanticised as destiny, but confronted as a preventable outcome.

Globally, creative markets increasingly prioritise financial literacy, contract transparency and mental health support as essential professional skills. Artists, who rely solely on applause, royalties and public sympathy, often face abrupt decline.

In South Africa, banks repossess homes, labels reclaim assets and silence replaces celebrity. The lesson is uncomfortable but necessary: success without structure invites downfall and survival narratives must not be mistaken for sustainability.

Yet collapse does not have to be permanent. Recovery begins with accountability, diversification and psychological recalibration.

Life coaching principles emphasise owning decisions, reframing loss as information and rebuilding systems before rebuilding image. Zola 7’s experience is instructive.

Once among South Africa’s highest-paid performers, poor spending choices dismantled his empire.

Reflecting later, he admitted that losing everything taught him discipline that fame never could.

His gradual return through community work, media projects and scaled-down living reflects global best practice.

Creatives must separate identity from income, maintain emergency savings, develop alternative revenue streams, hire professional managers and continually upgrade skills.

Rehabilitation, counselling and reputation repair should be treated as investments rather than shame.

Creatives must practise stardom management by living below their means and planning exits early.

Stardom is seasonal, but systems must endure. Preparedness, not deprivation, remains the only credible deliverance.