Deep in the gold-rich soils of Shurugwi, the clinking of picks and shovels at illegal mining sites echoes against the hills. But beyond the glitter of gold lies a silent battle — HIV.

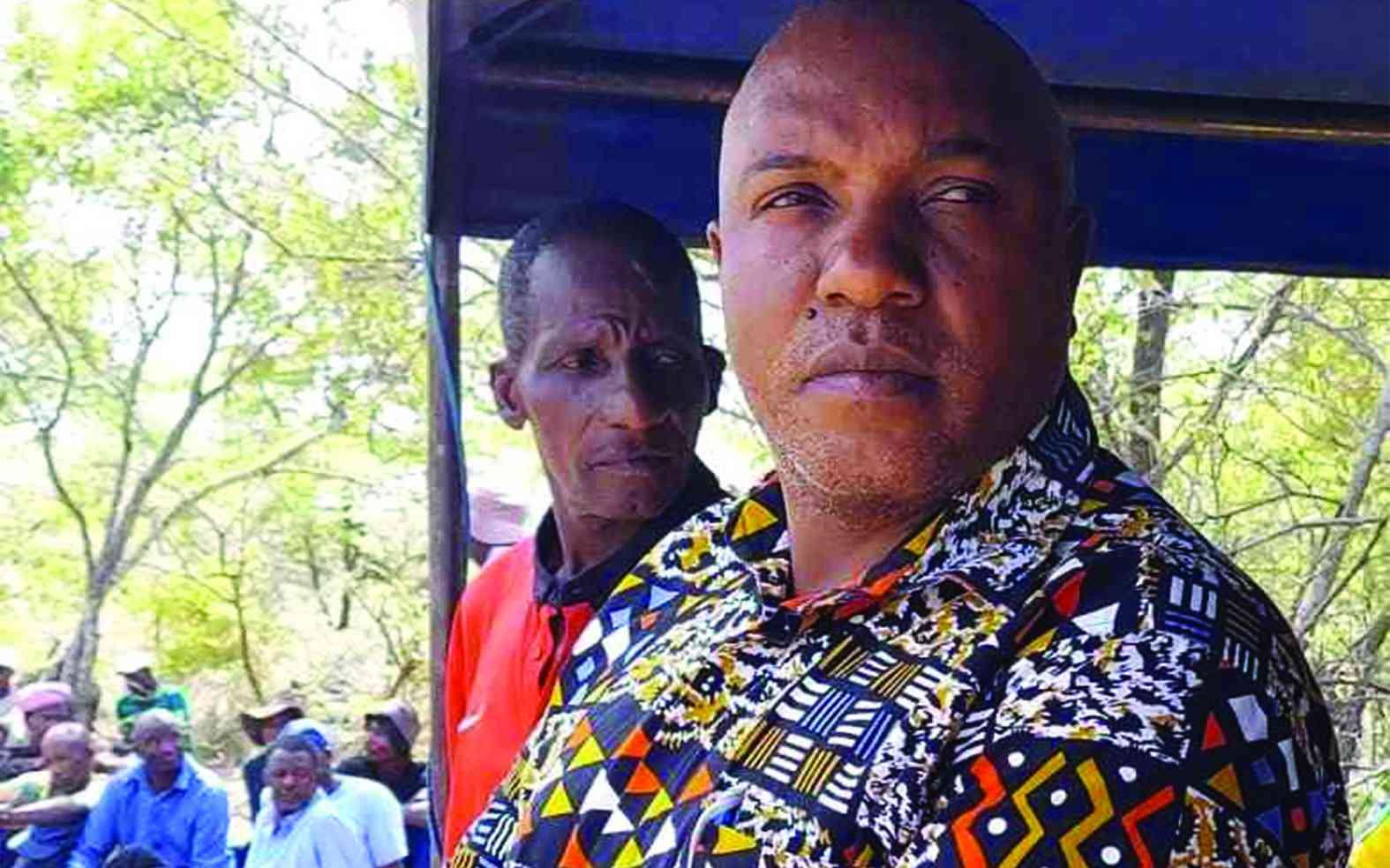

Shurugwi North legislator Joseph Mpasi says while mining has become the lifeline for many families, it has also contributed to the district’s high HIV prevalence.

“Shurugwi is a mining community and, naturally, the prevalence of HIV is high. I urge artisanal miners to seek health services where possible, get tested for HIV and STIs, and use protection when engaging in sexual activities,” Mpasi said.

“Government is scaling up mobile outreach programmes, and we are also constructing new health facilities to reach those in remote areas.”

For 28-year-old Tawanda*, an artisanal miner at Wanderer Mine, the struggle is real.

“We move from one site to another looking for gold. Sometimes we don’t even know where we’ll be next week. Going to the clinic is not always possible,” he admitted. “But I know it’s important to get tested and be safe.”

Women working around the mines face an even greater risk. Rudo*, a 32-year-old sex worker who operates at business centres around Shurugwi town, says she often negotiates for protection with clients.

“Some men refuse to use condoms, especially when they’ve been drinking,” she said.

- 57% of sex workers HIV positive

- Shurugwi North MP lays out 2024 vision

- Resource constraints hamstring HIV intervention programmes in Muzarabani

- Shurugwi MP bolsters community sustainability programmes

Keep Reading

“I try to insist, but sometimes it’s not easy. We want to live, we want to protect ourselves, but survival also matters.”

District Aids coordinator for Shurugwi Patience Muza says these realities shape how HIV interventions are designed.

“We are taking services to the people, right where they are. Mobile clinics and peer-led activities are critical for miners and sex workers. But the challenge remains: their mobility affects adherence to ART and continuity of care,” Muza explained.

Health workers and community peer educators are trying to bridge the gap.

At a recent outreach programme in Boterekwa, miners queued for HIV testing, while others attended discussions on prevention.

One of the peer educators at the site said stigma was slowly fading.

“At first, miners didn’t want to be seen near HIV tents. But now, they’re opening up. Some even encourage their colleagues to test together,” he said.

Despite these efforts, Shurugwi remains among the top three districts with the highest HIV prevalence in the Midlands province.

But for people like Tawanda and Rudo, access to health services gives them hope.

“We want to continue working, but we also want to live healthy lives,” Tawanda said, dusting off his hands after a long day underground.

*Not real name