ON the night of January 30 ,1985, Anna Ndebele’s husband Cephas was taken in for questioning by state agents in Silobela, in Midlands province, along with 10 other men.

They were never seen again. Thirty years later, the 74-year-old still doesn’t know where the remains of her husband lie.

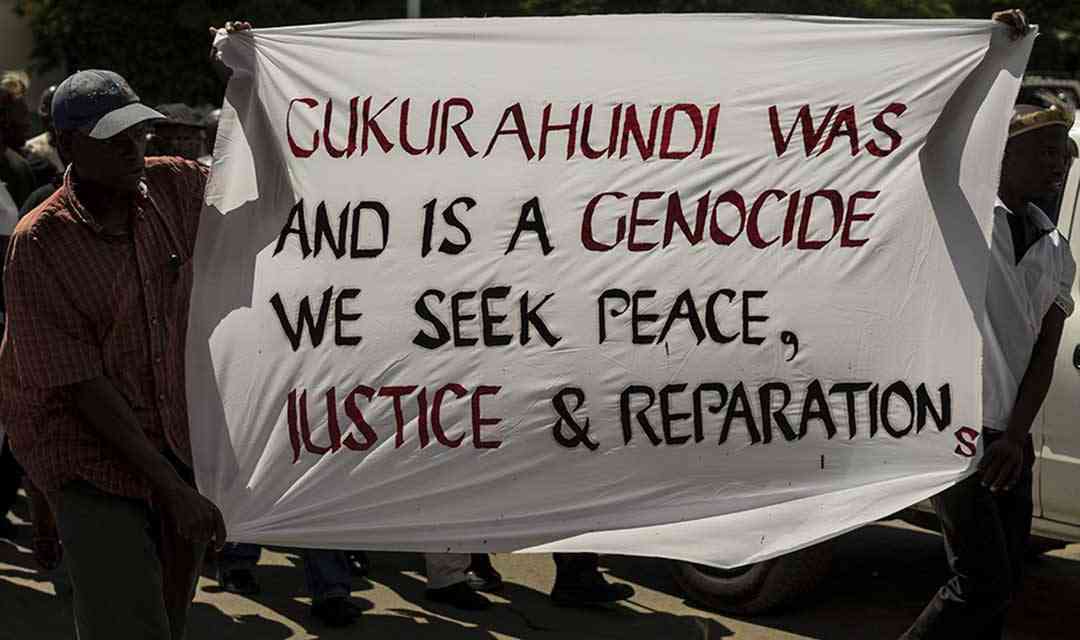

Some 20 000 civilians were killed in the Gukurahundi massacres from 1983 to 1987.

Families like Ndebele’s have lived in limbo, waiting to learn what really happened to their loved ones.

The Gukurahundi massacres stemmed from divisions of the Second Chimurenga, or Zimbabwe’s war for independence.

This conflict saw Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) and Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu) vie for power as both groups fought the white minority government.

After independence, Mugabe branded Zapu supporters as “dissidents”.

In 1983, he deployed the North Korea-trained 5th Brigade of the army to Matabeleland and the Midlands, home to the Ndebele and Kalanga ethnic groups.

- Ziyambi’s Gukurahundi remarks revealing

- Giles Mutsekwa was a tough campaigner

- New law answers exhumations and reburials question in Zim

- Abducted tourists remembered

Keep Reading

Thousands of people were “disappeared”, tortured, raped, or executed.

Mugabe later flippantly called the Gukurahundi (Shona for “the early cleansing rains”) campaign a “moment of madness”.

Today, community hearings are being held to document civilian experiences from that time.

Nearly 10 000 testimonies have been recorded. But the hearings are happening behind closed doors — with media, civil society, and many survivors excluded.

So far, they have been confined to Matabeleland even though atrocities also took place in the Midlands.

Ndebele says she holds little regard for the hearings anyway — and has only one request.

“We don’t want much: we want the bones of our husbands so we can hold them in our hands. If there’s anything else to be done, it can come afterwards – we don’t really care,” she says.

“But we want to know where these people went. We want their bones.”

A 1995 court order declared the Silobela Eleven presumed dead.

For Ndebele, grief for her missing husband was compounded by the death of her 11-year-old son, Paris, who was taken with the men and returned the next morning crying, bruised, and disoriented.

He died soon afterwards. Later, five soldiers attempted to sexually assault her.

“I screamed so loud they told me to keep quiet, but I couldn’t,” she says.

“They had taken my husband, killed my son, and now they wanted to rape me. These were gangsters, not soldiers.”

Every year, families gather to remember the Silobela 11 on January 30, the day they disappeared, or August 30, the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances.

At the first memorial in 2021, a plaque was erected, only to be destroyed overnight by suspected state agents.

A second plaque suffered the same fate. This year, flowers were laid on the rubble, as police interrogated villagers who had gathered.

The National Council of Chiefs, led by Chief Mtshane Khumalo, says the closed hearings are meant to protect the dignity and privacy of the survivors.

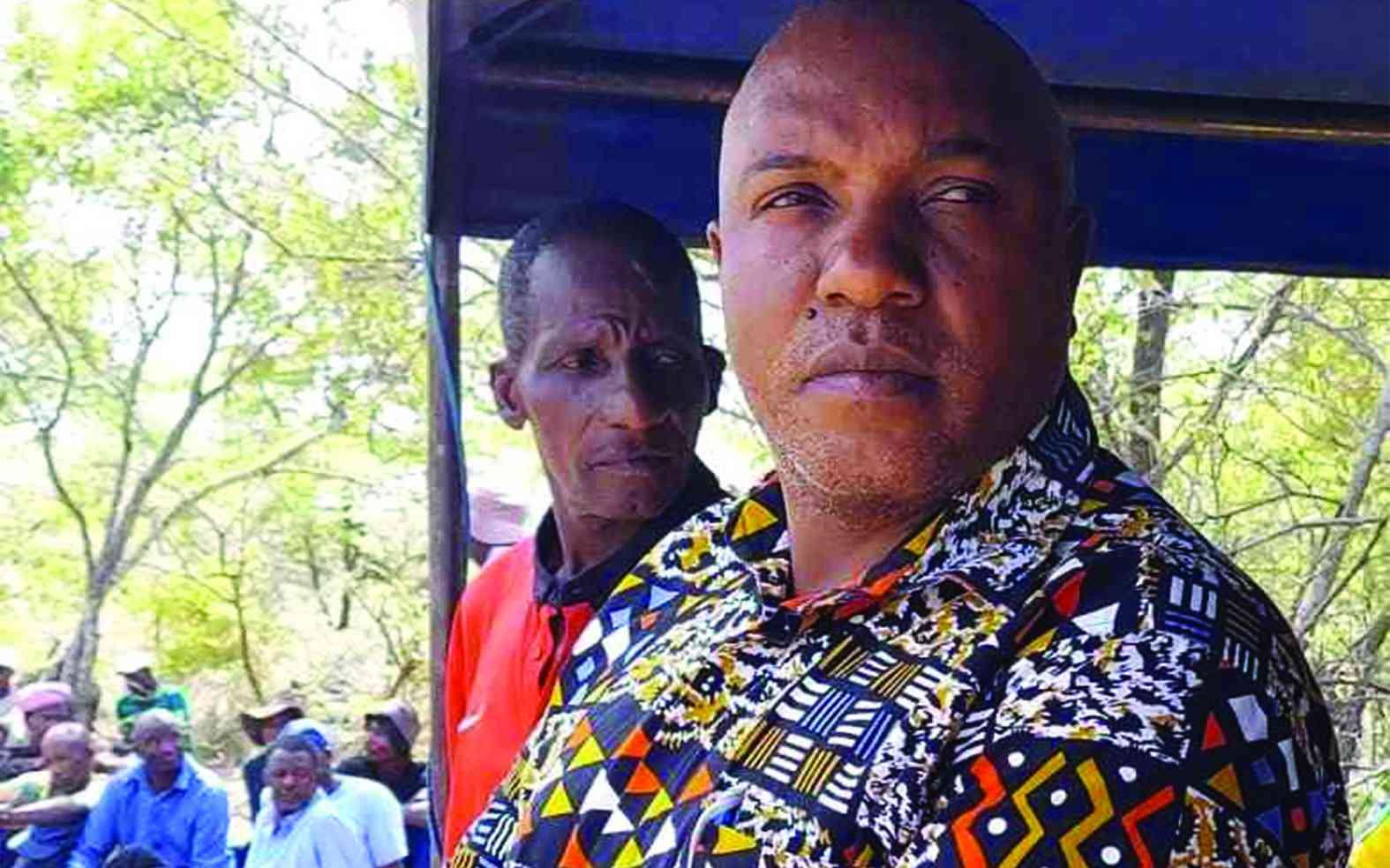

However, Mbuso Fuzwayo, head of Ibhetshu Likazulu, an advocacy group working with survivors, says the process is flawed.

“There is no transparency and the fact that this is excluding other stakeholders is clearly a micromanaged process,” Fuzwayo told The Continent. “It is not victim-centred.”

This is Zimbabwe’s third attempt at accountability for Gukurahundi. In the 1980s, Mugabe’s government established two commissions after the massacres, but both reports apparently vanished.

A few officials were charged with torture, none successfully prosecuted, and one case ended in an out-of-court settlement.

Today, President Emmerson Mnangagwa frames the hearings as a national turning point, where “the scars of yesterday no longer fester, but become stepping stones to a stronger, more unified Zimbabwe”.

Forty-two years later, Patricia Dlamini, 50, still bears the scars of Gukurahundi.

Her father, Alphion Bhelekwana Dlamini, was seized with other men on suspicion of aiding dissidents. Days later, his mutilated body was returned on a scotch cart, although the death certificate falsely asserted that he had been killed by crossfire.

Days later, his mutilated body was returned on a scotch cart, although the death certificate falsely claimed he had been killed by crossfire.

A few months later, the Fifth Brigade returned, forcing villagers to a meeting.

At just eight years old, Dlamini was beaten for failing to reveal rebel movements. Families were assaulted, livestock seized, and homes razed.

The Dlaminis fled to Bulawayo, surviving on handouts from the Catholic Church.

With six children to support, her mother could not afford school fees, and Dlamini dropped out at 15.

Now a housekeeper, she hopes today’s hearings will bring what she wants most — an apology and then compensation.

“We expect [that] whatever they give to people must be followed with the words, ‘I’m sorry’,” she says.

“If they don’t say sorry it will seem like the government is happy with what they did. Money won’t be enough to say sorry to us.”