In the gold-rich hills of Shurugwi, artisanal miners — commonly referred to as amakorokoza — toil daily beneath the earth’s surface in search of fortune.

But amid the glint of gold lies a dark, silent threat: a deadly trio of diseases — HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and silicosis — slowly eroding the lives and livelihoods of thousands in these informal mining communities.

A recent health survey among Zimbabwe’s artisanal and small-scale miners paints a grim picture.

The study found that 18% to 23.5% of miners are HIV-positive, 6.8% have active TB, and nearly one in five miners (19%) suffer from silicosis — a chronic and irreversible lung disease caused by prolonged inhalation of silica dust.

The average age of miners surveyed was just 35 years, highlighting the devastating impact of these diseases on a young and economically active population.

“The biggest danger is that many of these miners don’t even know they are sick,” says a health officer Shurugwi District Hospital.

“They work in dusty shafts, sleep in overcrowded shacks, and have little to no access to basic healthcare.”

The informal nature of artisanal mining makes it particularly dangerous. Without protective gear, miners breathe in silica dust from drilling and blasting — leading to silicosis.

- WhaWha triumphs in the slugfest of wardens

- Bruised Gems get consolation win

- Veld fires ravage Beitbridge

- Harare suspends Pomona deal

Keep Reading

Silicosis, in turn, weakens the lungs and greatly increases the risk of contracting TB. In miners living with HIV, the risk of TB becomes even greater.

Social conditions around mining sites also fuel the HIV epidemic.

Studies show that over 50% of miners engaging in extramarital sex do so without protection, and transactional sex is widespread.

Alcohol and substance abuse — often used to cope with the stress of mining — further hinder treatment adherence and increase vulnerability.

John*, a 32-year-old miner working in an unregulated pit near Musasa, was diagnosed with TB earlier this year.

“I thought it was just a cough,” he says, his voice raspy.

“I kept working. I had no money to go to the clinic. By the time I got help, I had already infected two people I worked with.”

The National Aids Council and other health partners are doing what they can.

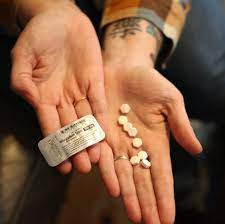

Through mobile outreach programmes, they now offer free TB and HIV screening, antiretroviral therapy (ART), treatment for silicosis symptoms, and basic health education.

Each mobile clinic sees up to 70 miners per day and over 200 community members, with thousands reached since the programme began.

Experts describe the situation as a public health crisis.

TB rates among artisanal miners in Zimbabwe are estimated at 7 400 cases per 100 000 people — a staggering 30 times higher than the national average.

In Shurugwi and other Midlands mining districts, health professionals fear the numbers are even higher due to underreporting and lack of diagnostics.

“This is not just a health issue; it’s an economic and social time bomb,” says development practitioner Takemore Mazuruse.

“When miners fall sick, families suffer, communities weaken, and the burden on already stretched rural clinics grows.”

Even more concerning, a large chunk of TB patients among miners have an unknown HIV status, complicating treatment and surveillance.

Despite the dire statistics, there is hope. Public-private partnerships, such as those encouraged by Joseph Mpasi, the Shurugwi North MP, are pushing for stronger health interventions in mining zones.

His efforts to attract investment in rural development have opened the door for improved healthcare access.

“We are working with the government to construct more health facilities in rural areas as well as in new resettlement areas,” Mpasi said.

“We encourage our artisanal miners to visit health facilities when they feel they are not well. It is also important that they go for HIV and TB testing.”

District Aids coordinator Patience Muza says these realities shape how HIV interventions are designed.

“We are taking services to the people, right where they are. Mobile clinics and peer-led activities are critical for miners and sex workers. But the challenge remains: their mobility affects adherence to ART and continuity of care,” Muza explained.

The Ministry of Health through the Stop TB initiative are working to establish more occupational health clinics — providing treatment not only for TB and HIV, but also for mining-related conditions like silicosis and hypertension.

The Union Zimbabwe Trust (UZT) with funding from the Stop TB Partnership (Global) in August launched an innovative TB screening outreach project to promote early detection and treatment in high-risk artisanal mining communities of Mberengwa and Zvishavane.

Mary Muchekeza, Midlands provincial medical director described this outreach project as a game changer in the diagnosis of TB and silicosis particularly in settings like mining communities targeting artisanal miners and ex-miners.

As Zimbabwe marches toward Vision 2030, the plight of artisanal miners must not be ignored.

They are the engine of rural economic activity — but unless urgent action is taken, their dreams of prosperity will remain buried beneath the dust.

“We dig for gold, but we are digging our graves too,” says John. “We just want to live.”

*Name protected