Between dusty roads linking Gwenika in Gokwe South and Sanyati in Mashonaland West, villagers say the constant roar of heavy trucks hauling ore and stone has become more than a nuisance — it is making people sick.

Villagers of Masoro in Gokwe South’s ward 24 and neighbouring settlements blame clouds of fine dust kicked up by frequent haulage from Chinese-operated mining sites for a sharp rise in coughs, chronic respiratory problems and, they claim, tuberculosis (TB).

TB and dusty environments are linked because inhaling certain dusts, especially silica dust, significantly increases the risk of developing tuberculosis.

This phenomenon is known as silicosis-tuberculosis, where the dust damages the lungs, weakening the immune system's ability to fight off the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, making exposed individuals much more susceptible to the disease.

“Tins of dust settle inside the houses every evening,” said Tinashe Jani, a Masoro villager.

“You can taste dust on your food. We cough all the time. People we know get sick and when they go to the clinic they are told it is TB. Since the trucks started coming here the sickness is worse.”

For communities that live and work beside unpaved roads and informal mining corridors, the visible clouds of grit are only the most obvious sign of a deeper danger: microscopic silica and other respirable dust particles that penetrate deep into lungs and increase vulnerability to TB and silicosis — a disabling, irreversible lung disease.

A growing body of research links silica exposure in artisanal and small-scale mining to higher rates of both silicosis and TB.

- Vaccination programme brings relief to Midlands cattle farmers

- EU project brings smiles to Gokwe farmers

- Bantuman I introduces schools festival

- Vaccination programme brings relief to Midlands cattle farmers

Keep Reading

Villagers walk the same routes used by the heavy haulage trucks. Some report that the trucks fail to cover loads or use inefficient speed and braking practices that raise dust.

Women say dust settles on cooking pots and on babies’ faces; farmers complain of reduced yields when dust smothers new seedlings.

“After the trucks pass, my chest tightens,” said another villager.

“Our clinic at Gwenika is small — people wait, cough and then they go home with medicine. But the cough comes back.”

Local elders and community health volunteers said they have seen dozens of chronic cough cases in the past few months, a worrying trend in a district already burdened by climate change.

Zimbabwe continues to carry a significant TB burden even as progress is made in diagnosis and treatment.

Recent national estimates put Zimbabwe’s annual TB incidence in the tens of thousands of cases; global reporting shows TB remains one of the world’s leading infectious killers, with millions of cases annually.

Locally, studies of artisanal miners in Zimbabwe have documented alarmingly high rates of TB and silicosis, making miners and communities around mines a high-risk group.

International research has repeatedly shown that inhalation of silica dust increases the risk of developing TB, and that miners working in informal, unregulated conditions face the greatest exposures.

Reductions in respirable crystalline silica exposure are associated with fewer cases of silicosis and TB, according to modelling and field studies.

Community leaders say the bulk of heavy haulage servicing mines around Masoro is contracted to Chinese operators.

Villagers report little consultation with local authorities when routes were upgraded for heavy traffic, and complain of inadequate road maintenance and lack of dust suppression measures (such as water spraying or covered loads).

Attempts to contact representatives of the mining companies operating in the area were unsuccessful at the time of reporting.

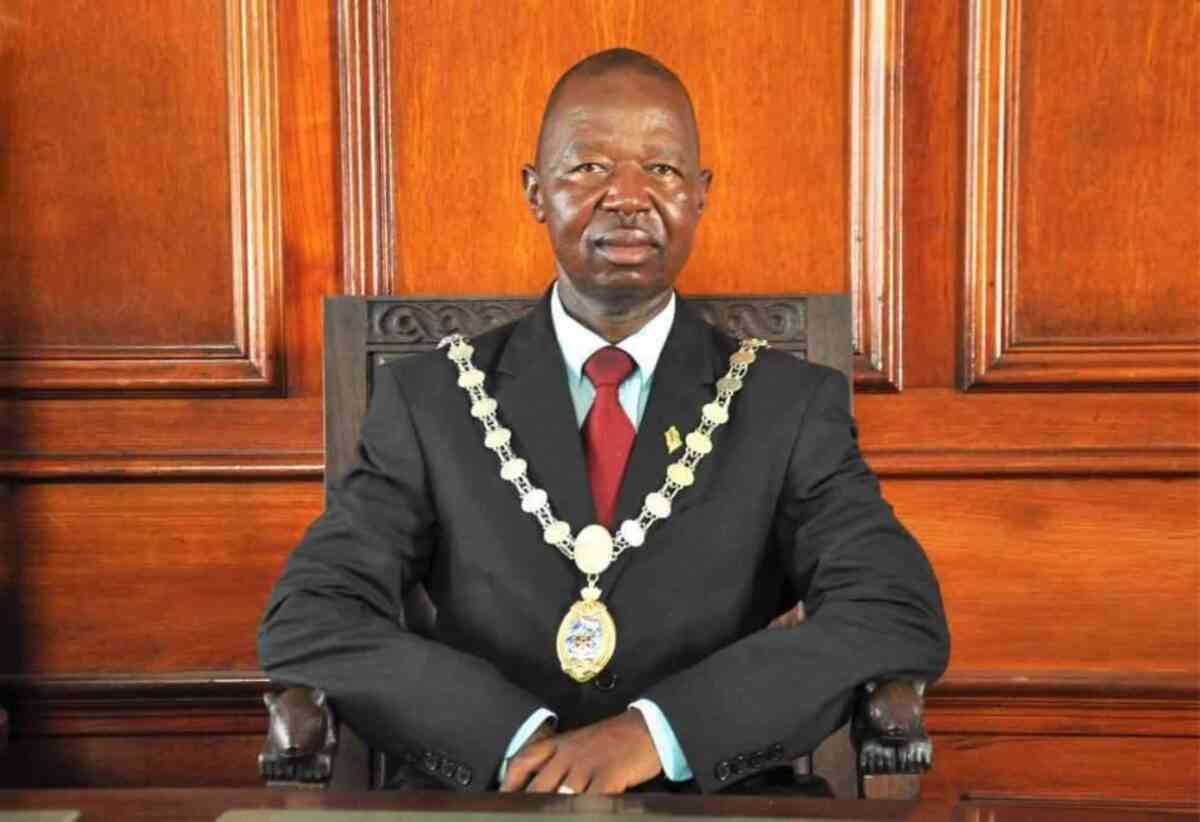

Ward 24 councillor Cosmus Maketo said he was aware of complaints and they will engage the miners to abide to haulage and environmental regulations.

Medical doctor and health expert Johannes Marisa said dust containing silica particles causes lung inflammation and scarring that reduces the organ’s ability to fight infection.

“Dust particles are quite dangerous as they make their way through the airways to settle on the lungs,” Marisa said.

“There are dangers that diseases like asthma and pneumonia can gradually appear. Since silica is found in sand, clay or gravel; continuous inhalation can result in silicosis, a severe lung disease characterised by inflammation and scarring. As such, chances of getting TB arise as well.”

People with silicosis — or even those with heavy, but subclinical silica exposure — have a markedly higher risk of contracting TB if exposed to the bacterium.

In informal mining contexts where workers live in crowded accommodations and health services are distant, the triple burden of silica exposure, HIV and TB is a documented crisis.

For families like the Janis, the impact is immediate: lost income, long clinic queues, months on TB treatment and the strain of caring for sick relatives.

Health and occupational specialists said tackling the problem requires a mix of short- and long-term measures: rapid expansion of mobile TB screening and GeneXpert diagnostic capacity along mining corridors; regular community health education; suppression of dust on haul routes (watering, speed limits, covered loads); proper personal protective equipment for workers; and stronger enforcement of environmental and occupational safety standards.

International evidence shows that relatively simple engineering controls in mines and on haul roads can dramatically reduce inhalable dust and long-term disease.

Public health officials said they were constrained by resources, but that the Health minitry, partners and donors are expanding targeted outreach to mining communities.

National Aids Council’s Gokwe South district Aids coordinator Isaki Chiwara said his organisation was fostering a multisectoral approach.

“As part of outreach programmes alongside the Health and Child Care ministry, we make sure that our programmes incorporate HIV testing and TB screening, among other services,” he said.

The Ministry of Health and Child Care leads TB control by implementing the National TB Strategic Plan (2021-2025), which aligns with the global End TB Strategy.

Key activities include adopting shorter tuberculosis preventive therapy regimens, especially for people with HIV, strengthening contact tracing, and integrating an adapted WHO Prevent TB Application to accelerate TPT rollout.

The Health ministry also focuses on policy development, disease monitoring, resource allocation, and workforce planning through its Aids and TB unit, all in collaboration with partners like the WHO and The Union Zimbabwe Trust.