The road stretches ahead, long and grey, with trucks rumbling past and a haze of dust hanging thick in the spring air.

For residents along the Bulawayo–Victoria Falls highway, the journey is not just about reaching a destination — it’s about surviving each passing cloud of grit.

For years, Zimbabweans have lamented the state of this vital corridor linking the south to the north. Potholes, washaways, and bumpy journeys were the norm.

In response, the government embarked on an ambitious rehabilitation project, hiring contractors to repair, widen, and upgrade sections of the highway.

To keep traffic moving, more than five detours have been constructed along different stretches.

But for the people living alongside the detours, progress has a heavy, dusty price. Trees, which should be sprouting fresh leaves, are coated in brown powder.

Grass struggles to grow.

Homes, many built facing the road, are constantly battered by clouds of grit.

Masks have become a daily necessity for some, for others, poverty forces them to endure the haze.

Trucks, buses, and other vehicles stir the fine powder into temporary dust storms that leave throats parched and eyes stinging.

“We are happy that the road is finally being fixed after so many years, but the dust has made life unbearable,” said Gogo MaNdlovu, 72, whose homestead sits just meters from the first detour before Benice (KoBhinisi).

“Every morning I wipe my furniture and within an hour it’s covered in dust again.

“My grandchildren cough all night.

“Even our eyes sting and tear from the dust.”

Sibongile Dube, a young mother of two, explained how she copes.

“I wear a mask almost every day, even when I’m just sweeping the yard,” Dube said.

“When trucks pass, the whole place becomes foggy with dust.

“My little boy has constant flu and I suspect it could be from the air we breathe.

“Sometimes they sprinkle water, but when they don’t, it’s terrible. It has been a long time since the last sprinkling.”

Even schoolchildren are not spared.

A Form Two student from a local school said they cover their faces with cloth as they head to school.

“When we walk to school, we cover our faces with cloth,” she said.

“Sometimes the trucks pass so fast we can’t even see the road for a few minutes.

“Our uniforms are always dirty and our throats feel dry and sore by the time we reach class.”

Farmers lament the damage to crops and trees.

Mgcini Zulu, a small-scale farmer, said the trees were no longer green — everything is coated in a layer of brown dust.

“Even the vegetables in the garden are suffering,” he said.

“You can’t even hang clothes outside because they get dirty before they dry.

“We understand that roads bring development, but this stage is too painful.”

He added that the dust affects his animals just as much as it affects humans.

“They cough and sneeze when the trucks pass, and sometimes their feed gets covered in dust before they can eat,” Zulu lamented.

“I never thought roadworks could make life so hard for our animals.”

Even fruit trees are under siege.

“Our mango and guava trees are covered in thick dust. Leaves are brown and dry, and some fruits fall off before ripening,” he said.

“Even the vegetables in our gardens struggle to grow.

“The water they sprinkle sometimes helps, but not enough.

“When it doesn’t rain, the dust destroys everything.”

Vendors like Nomusa Moyo also bear the brunt, spending the whole day inhaling dust.

“Sometimes my chest feels tight and I start coughing,” Moyo said.

“We have tried asking the workers to water the road more often, and sometimes they listen, but other times they just say the tanker has gone to refill.

“So we just endure and hope this will soon end.”

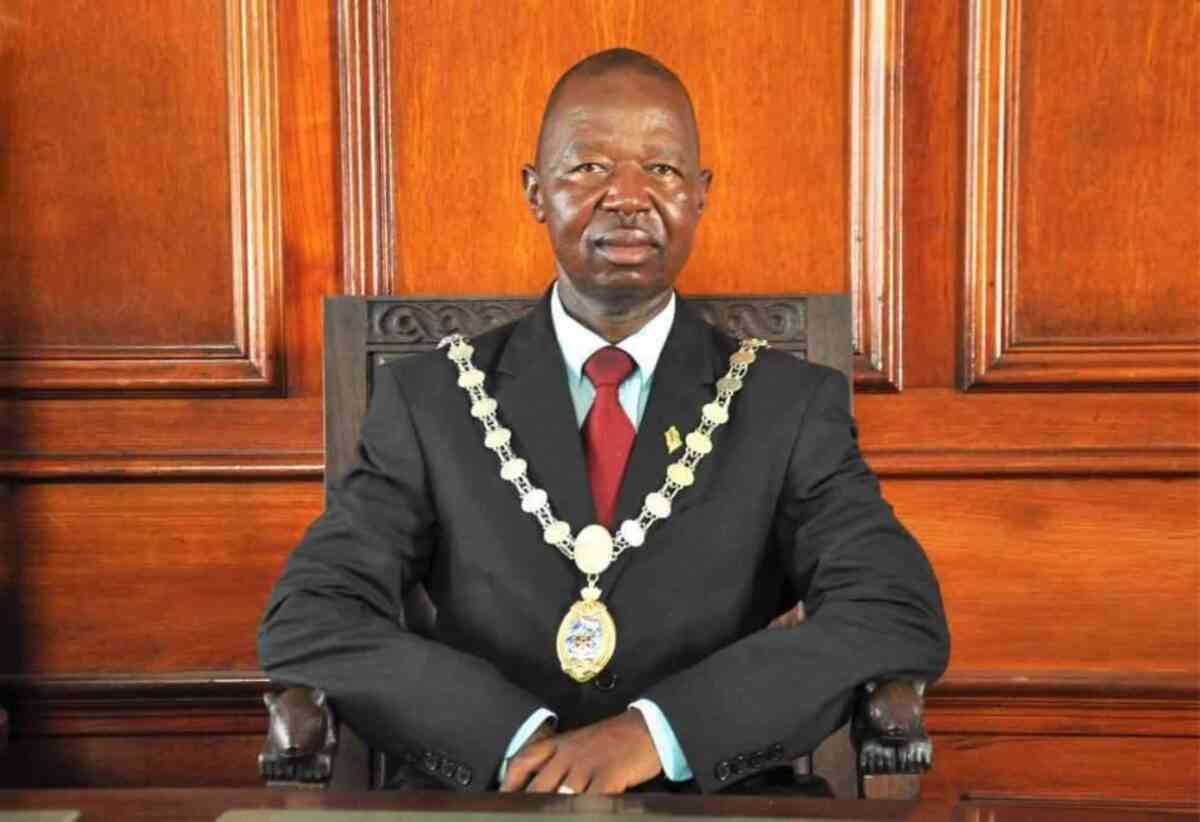

Provincial Affairs and Devolution minister for Matabeleland North, Richard Moyo, acknowledged the complaints saying he will make a follow up with the engineers.

“The contractors seem to be doing their own thing, but as the government, we encourage them that wherever they put detours, they must ensure that water trucks are used to prevent dust from affecting surrounding communities,” Moyo said.

“I will speak with the engineers and remind them to ensure that water is always poured on the detours.”

Experts warn that the problem goes beyond mere inconvenience.

Bulawayo-based social commentator Effie Ncube explained that the dusty conditions were almost inevitable in Matabeleland North, where the soil is sandy and highly prone to producing dust once roads are cleared and opened to traffic.

Trucks, buses, and other vehicles stir fine particles into the air, creating health hazards and reducing visibility.

“The dust coming from unpaved detours contains inhalable allergens and pathogens that can trigger respiratory problems, worsen conditions such as asthma, and even increase the likelihood of accidents because drivers’ visibility is reduced,” Ncube said.

“It also settles on trees, crops, and nearby water bodies, threatening local ecosystems.”

He emphasized that solutions are available and widely used globally.

Wet water suppression — spraying unpaved roads with water — is a simple, environmentally-friendly, and cost-effective method to bind dust and prevent it from rising.

Regular use, he explained, can protect both public health and the environment while keeping roads clearer for drivers.

On Monday, the Ministry of Transport said only 19.2 km of the Bulawayo-Victoria Falls highway had been rehabilitated, leaving a balance of work of 421.2 km.