The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) has announced the official results of the 7 May 2022 local authority by-elections, filling council vacancies across several provinces including Harare Metropolitan, Manicaland, Mashonaland Central, and Mashonaland West. While the results were released in accordance with electoral procedures, the process surrounding the by-elections has raised renewed concerns about the integrity of elections conducted under conditions of intimidation, coercion, and political violence—particularly in rural areas.

The by-elections came just weeks after the March 2022 parliamentary elections, in which the opposition Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) made significant gains nationwide. The results appeared to unsettle the ruling ZANU-PF party, especially in provinces long considered its political strongholds. Mashonaland Central, where political loyalty has historically been enforced through informal structures and coercive practices, emerged as a focal point of tension in the lead-up to the May polls.

According to ZEC notices and published results, candidates from ZANU-PF, CCC, and smaller parties contested council seats across multiple wards. However, civil society organisations, community leaders, and residents interviewed in the aftermath say the voting took place in an environment where free political choice was severely constrained.

An Environment of Coercion

In the weeks preceding polling day, reports from Mashonaland Central indicated a sharp escalation in political mobilisation by ruling-party aligned youth groups and informal militias.

Villagers described being compelled to attend political meetings, sometimes under threat, and warned that failure to demonstrate loyalty would have consequences. Several residents said headmen and local leaders were instructed to ensure full attendance at ZANU-PF rallies and to identify households suspected of supporting the opposition. In farming communities, political compliance was closely linked to continued access to land, agricultural inputs, and basic services.

“Everyone knows that being opposition in the rural areas is dangerous,” said one community member, speaking anonymously. “You keep quiet or you suffer.”

The Chomumwe Chesa Farm Attack

- RG's Office frustrating urban voters: CCC

- Fast-track delimitation, Zec urged

- 'Political parties must not be registered'

- Zec to address nomination fees outcry

Keep Reading

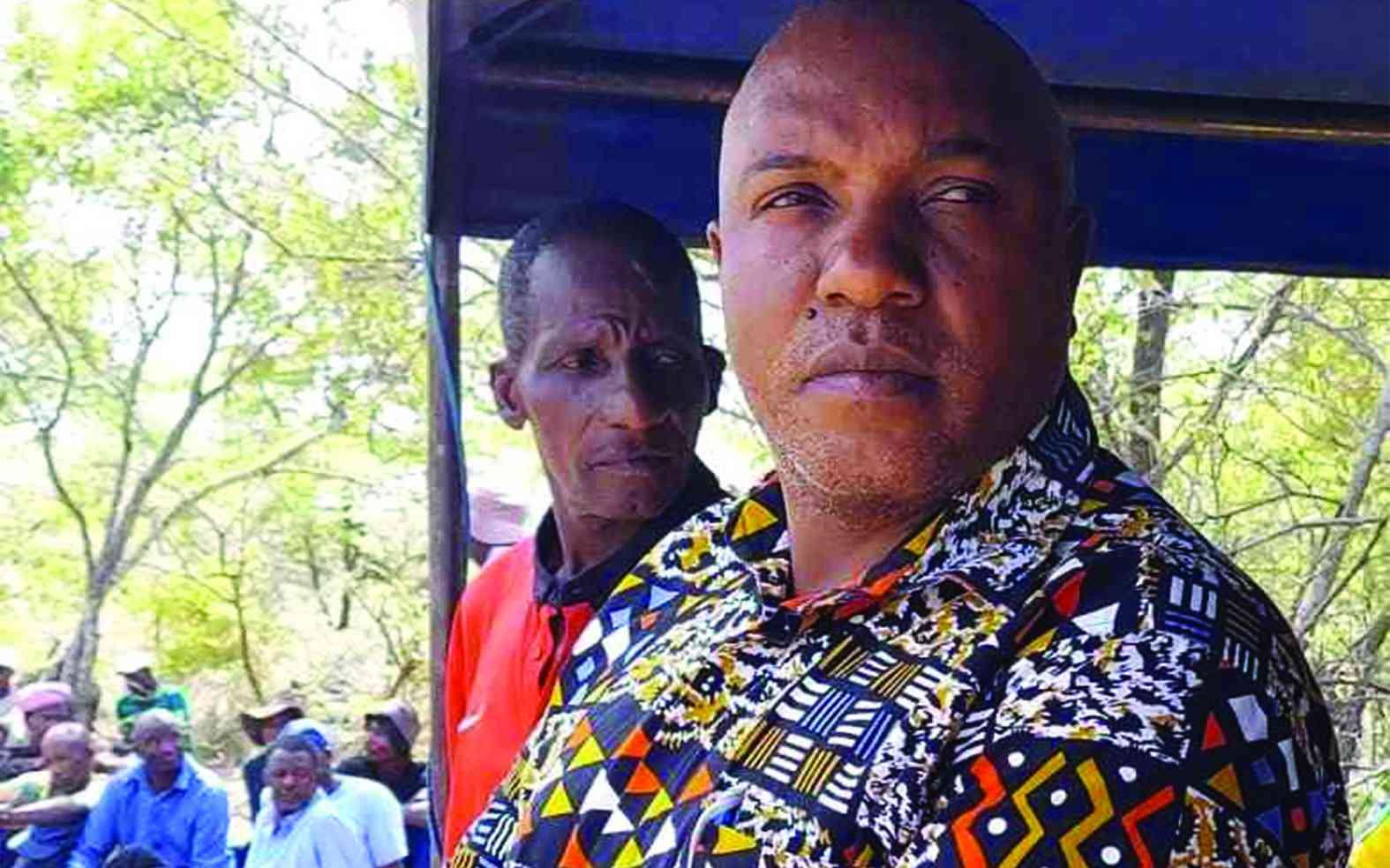

Against this backdrop, a serious incident was reported at Chomumwe Chesa Farm, a long-established family farm in the Mt Darwin area of Mashonaland Central. According to multiple villagers who spoke on condition of anonymity, a farmhouse on the property was deliberately set on fire late at night in the days leading up to the by-elections.

Residents said the incident followed heightened political pressure in the area, including threats that individuals perceived to be sympathetic to the opposition had “no right to farmland” and that such land should be reclaimed. These claims were reportedly made openly during political meetings and informal gatherings.

“We heard people talking earlier that day,” said one villager. “Later, around midnight, there was fire. The flames were already high when we noticed.”

Another resident said they saw a vehicle leaving the vicinity shortly after the fire started but could not identify the occupants. Fear prevented neighbours from intervening or approaching the scene.

“During elections, you don’t ask questions,” the villager said. “You pretend you saw nothing.” There is uncertainty as to whether the occupants of the farm—identified locally as Maxwell Chomumwe, his wife Memory, and their young daughter—were present in the house at the time of the fire. Some villagers believe the family may have fled earlier that evening, while others say they do not know if anyone was inside when the fire was set. What is clear, residents said, is that the family left the area immediately afterward.

Attempts by journalists and local organisations to contact the Chomumwe family were unsuccessful. Neighbours reported that the family went into hiding following the incident, and

their whereabouts were unknown at the time of writing. Local sources described the farm as a “no-go area” after the attack, with residents avoiding the property out of fear of further violence.

A Pattern Repeated

Human rights observers note that the Chomumwe Chesa farm incident reflects a broader pattern seen during election periods in Zimbabwe, where land and political loyalty are tightly intertwined. Allegations of “land disputes” often emerge around election cycles, frequently masking politically motivated attacks on individuals or families perceived to support the opposition.

“These incidents are rarely isolated,” said a civil society activist familiar with rural Mashonaland. “They send a message to the entire community.”

Reports of intimidation and violence were not limited to one location. Across Mashonaland Central and parts of Mashonaland West, residents spoke of beatings, threats, and forced

political participation in the days before the vote. Some families reportedly fled their homes temporarily to avoid confrontation.

Polling Under Surveillance

On polling day itself, voter turnout varied significantly. While some urban wards experienced relatively orderly voting, rural polling stations were described as tense. Observers reported the presence of individuals loitering near voting centres, monitoring arrivals and departures.

Several voters said they felt compelled to vote to avoid suspicion or retaliation. Others said they attended polling stations simply to be seen, believing that absence would be interpreted as opposition support.

ZEC later announced results showing victories for both ZANU-PF and CCC candidates across different wards. Analysts caution, however, that the figures cannot be viewed in isolation from the environment in which the elections took place.

“Elections held under fear cannot be considered fully democratic,” said one political analyst. “The results reflect not only political preference but also survival strategies.”

Aftermath and Displacement

In the aftermath of the by-elections, reports emerged of families displaced from their homes, disrupted livelihoods, and children unable to attend school due to security concerns. In several cases, victims avoided reporting incidents to the police, citing lack of trust and fear of further reprisals.

For families such as the Chomumwes, neighbours say the consequences were immediate and severe. With the farm no longer safe, the family disappeared from the area entirely.

Calls for Accountability

Civil society organisations have called on authorities to investigate reports of election-related violence and intimidation and to ensure protection for affected communities. They warn that without accountability, such practices risk becoming further entrenched ahead of future national elections.

ZEC has stated that it conducted the by-elections in line with the law, while ZANU-PF has dismissed allegations of systematic intimidation as exaggerated or politically motivated.

For many rural voters, however, the May 2022 by-elections reinforced a familiar reality: that political participation in Zimbabwe often comes at a high personal cost. As one villager in Mashonaland Central put it quietly, “You can vote—but only if you are

prepared to lose everything else.”