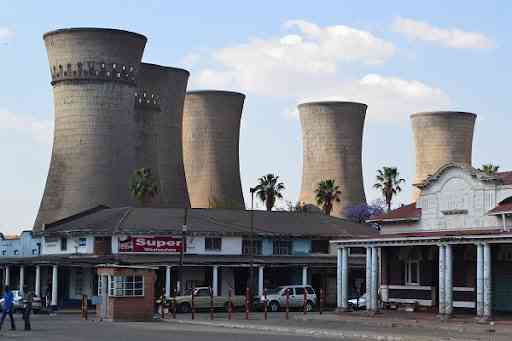

Bulawayo’s industrial collapse is one of the most tragic and telling chapters in Zimbabwe’s economic history.

Once celebrated as the country’s manufacturing powerhouse, the city now bears the scars of neglect, policy failure and unresolved political questions.

While sanctions have often been presented as the primary cause of this decline, they tell only part of the story.

The truth is more uncomfortable: Bulawayo was allowed — and in some instances seemingly designed — to deindustrialise.

For decades, Bulawayo anchored some of Zimbabwe’s most strategic industries. The National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ), headquartered in the city, was once the backbone of regional trade and employment.

Today, the rail utility is a shell of its former self, crippled by underinvestment and mismanagement.

Major manufacturing giants such as Treger Products, Merlin, Hunyani, Dunlop and the Cold Storage Commission (CSC) either closed their doors, relocated, or drastically scaled down operations, wiping out thousands of skilled jobs and hollowing out the city’s industrial base.

- Revisiting Majaivana’s last show… ‘We made huge losses’

- Edutainment mix: The nexus of music and cultural identity

- ChiTown acting mayor blocks election

- Promoter Mdu 3D defends foreigners 30 minute set

Keep Reading

Government officials, including Zanu PF Bulawayo provincial chairman Jabulani Sibanda, have blamed sanctions, arguing that restrictions imposed by former colonial powers limited access to machinery and capital, much of it sourced from countries like Britain.

While sanctions undoubtedly created challenges, they cannot fully explain why Bulawayo suffered more severely than other industrial centres.

Leadership is measured by its ability to adapt under pressure, yet Bulawayo was starved of the innovation, retooling and policy support necessary for survival.

Former Speaker of Parliament Lovemore Moyo’s assertion that Bulawayo’s decline was driven by deliberate political and tribal considerations raises troubling questions.

The relocation of company headquarters to Harare, the drying up of state contracts, and the absence of targeted infrastructure investment reinforce perceptions of systematic marginalisation.

As factories closed, unemployment surged, forcing generations of skilled workers to migrate to South Africa, Botswana and beyond in search of livelihoods.

The collapse of Bulawayo’s industry is not merely an economic failure; it is a governance failure.

Crumbling infrastructure, erratic power supplies, corruption and policy inconsistency have repelled investors and accelerated decay.

Reviving Bulawayo demands more than rhetoric and blame-shifting. It requires honest introspection, equitable national development policies, massive infrastructure investment and the political will to restore the city’s rightful place in Zimbabwe’s economy.

Without decisive action, Bulawayo risks becoming a permanent symbol of squandered potential rather than a catalyst for national renewal.