SEVERAL weeks ago, a media training and sensitisation workshop afforded a group of journalists from all over the country a chance to interview and listen to the testimonies of sex workers.

The generality of society views sex workers with intense aversion and the stampede for the moral high ground each time the phrase “sex work” or more commonly “prostitution” is mentioned attests to this.

I have always had a problem with legislating morality because moral values and their enforcement can only be instantiated from a premise that assumes homogeneity among all members of society — and such an assumption is obviously unsound.

I have several defences for the sex work trade, but I am writing in this instance to challenge the unfounded notion that sex is only permissible when it is transacted as an act of love and not through any other mutual and consensual agreement between the adults who engage in it.

Sex is a currency. Some people use it to buy love and affection or to sustain the same. Others use it to exchange the bodily fluids necessary to reproduce for noble and not-so-noble motives including forcing a man to marry them or confining a woman in the domestic sphere by turning her into a baby making machine.

Some people use it as leverage to control the purse strings of the men who lust after them and others use it to exercise control over the women who are financially dependent on them.

Some people use sex to express love and affection, others wield it as a weapon to subdue the women or men that they want to take advantage of.

From the time a young man learns to woo a young woman, he is made to believe that his quest is to find a transactional commodity that the young woman will find agreeable and terms upon which she will accept him as a suitable partner.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In time, young women are taught to withhold their bodies until the young men offer a higher commodity to transact with — the offer of marriage.

Society agrees that the only acceptable transactional arrangement to facilitate the enjoyment of sex is marriage and therefore it becomes the goal of every mother to preach abstinence to her daughter and every father to preach material gain to his son so that the pair can negotiate from a common premise in future.

To marry, the young man must have money and to get married. The young woman must have something valuable to bargain with – her virginity or her body.

It is not true that sex is only about love. Sometimes it is about pleasure. At other times it is about comfort and companionship. At other times it is about procreation. And in a society where poverty is rife, sex can be about money, about the bread and butter issues, and about survival.

In a materialistic society lying on one’s back can be about financial gain and a lavish lifestyle paid for through sex. Tradition, religion, the law, rightness and wrongness and the moral code of a given society may prefer to couch sex in different ways depending on the ideal that each institution pursues, but none of them should presume homogeneity.

Listening to the tales of those sex workers, I struggled with my prejudices, struggled to put myself in these women’s shoes until I gave up the attempt altogether. I felt sympathy, but not empathy because their lives and experiences were so far removed from my own that I was willing to consider myself quite unqualified to judge them or the choices they have made, but having heard their side of the story, I consider myself qualified to defend them.

What qualifies you to judge? Is it your high moral code? Is it your Christianity or religious belief? Is it your traditional values or cultural norms? Is it your infallible sense of knowing right from wrong?

People qualify themselves to judge by stripping away any recognition of the humanity of sex workers, viewing them as vermin that should be exterminated at best or punished at the very least.

Sex workers are ordinary people. They are as ordinary as the clients they service. For every sex worker, there is an employer.

If what qualifies one to judge is a moral code, then why is this morality or self-righteous indignation not directed towards the root causes of sex work such as poverty, or why is it not directed at the clients who keep these women on the streets by making sex work a viable option?

Why is it not translated into positive action that can reintegrate these sex workers into society rather than increasing their vulnerability through societal ostracism?

If your own aversion to sex workers is influenced by religious beliefs, traditional values or an internalised societal standard of what is right or wrong, then you must remember that your religious beliefs are your own, the traditional values you choose to embrace are not compulsory for the next person and your idea of what is right or wrong is informed by your own lived experience – which is not universal.

If you can trace every sexual encounter you have ever had to some “noble” transactional arrangement such as love or marriage, then good for you but in the real world, people have sex for many reasons and financial gain is one of them.

Turning up your nose at a sex worker without extending similar contempt to those who pay for sex is just an expression of misogyny and hypocrisy because you’re saying that the one who chooses to sell sex is less than the one who equally chooses to buy it.

Would sex work exist if each sex worker had sex all by herself? Clearly not, because for every sex worker there is an employer.

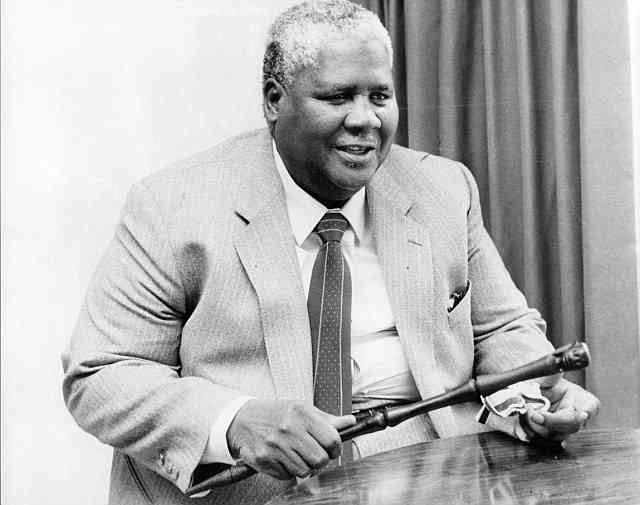

Delta Milayo Ndou is a journalist, writer, activist and blogger