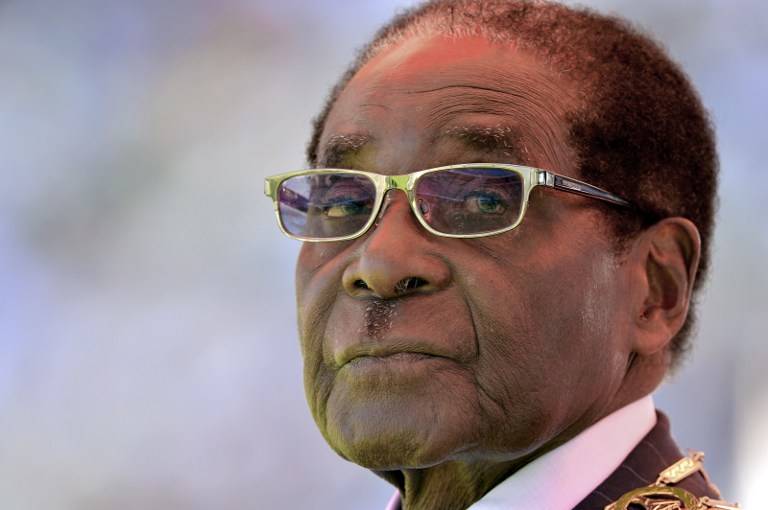

THE broad avenues lined with lilac trees in Harare show no images of 91-year-old President Robert Mugabe, but his presence towers over the country he has ruled for 35 years.

Agencies

“The whole country is on standby. We are just waiting for him to die,” said Evans, a taxi business owner.

Complaints abound about Mugabe’s authoritarian rule, which is seen as having ravaged what was once one of the region’s most promising economies.

But the president, who participated in the liberation struggle against white minority rule in the 1960s and 70s and seized the land of about 6 000 white farmers to redistribute it to more than 240 000 blacks, also commands respect.

“He has done more to empower black people than any other African leader,” Evans admitted.

The expulsion of experienced white farmers contributed to a decade-long crisis that cut the economy by half and forced Zimbabwe to replace its inflated currency with the US dollar in 2009.

Western sanctions over human rights violations, indigenisation laws requiring that 51% of major companies must be owned by locals, and massive corruption have scared investors away.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Less than 700 000 people are officially employed, said Gideon Shoko, deputy secretary general of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions.

That leaves about 80% of the workforce struggling to make a living in the informal sector, far above the official unemployment rate of 11%.

Children reduced to beggars

A plunge in maize production and the high prices of food imported from South Africa have aggravated the situation of many families, which may skip meals and not have money to send their children to school, according to locals in Harare and Victoria Falls.

Children beg under Harare’s traffic lights. Some women are resorting to prostitution, while poorly paid police officers erect road blocks to extract bribes from motorists, residents said.

Health centres treat poor people in exchange for their relatives cleaning wards.

“A few of my relatives died because of lack of money for treatment,” businessman Norest Marara said. Power cuts paralyse an industrial sector running at less than 40% of its capacity, according to the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries.

Some Harare neighbourhoods only have electricity between 10pm and 6am, with women cooking on fires in yards where people chat in the dark.’

“Mugabe may not last much longer,” a Western diplomat said about the veteran leader who falls asleep at public functions, read the same speech twice, and reportedly keeps travelling to Asia for medical treatment.

“Everything here revolves around one man. And when he goes, a volcano will erupt,” said Obert Gutu, spokesman for the main opposition party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC).

In its decades in power, Mugabe’s Zanu PF has taken the country firmly in its grip, ranging from state-owned companies to local chiefs and farmers who say they vote for the ruling party for fear of losing their land that officially belongs to the state.

Demonstrations are repressed with a heavy hand.

At least three government critics have disappeared and more than 100 people have been charged with insulting the president over the past five years, while journalists keep getting arrested, said KumbiraiMafunda from Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights.

Power struggles Mugabe has refused to name a successor, allegedly to give his family time to secure its wealth.

“He is a Machiavellian strategist who pits Zanu PF factions against each other,” said political analyst Eldred Masunungure from the University of Zimbabwe.

A power struggle is reportedly raging between Mugabe’s deputy Emmerson Mnangagwa and a group of ambitious politicians, including Higher Education Minister Jonathan Moyo and former minister Saviour Kasukuwere.

The group is pretending to campaign for the presidency of first lady Grace Mugabe in an attempt to sideline Mnangagwa, according to analysts.

After Mugabe dies or retires, “we may see violence” between Zanu PF factions, Gutu said.

Analysts say the party may win the 2018 elections with rigging and intimidation — but it also enjoys real support.

“When Mugabe dies, many people will shed genuine tears,” Masunungure said, adding that the much-criticised president will also leave a positive legacy.

He is seen as having improved education and health care in the country with a literacy rate of 90% — high for Africa. The land redistribution — despite its chaotic and sometimes violent nature and favouritism to Mugabe’s cronies — is widely seen as an act of social justice.

“There is a consensus that it had to be done,” Gutu said.

Mnangagwa — a former intelligence chief associated with violent crackdowns on the opposition — is likely to succeed Mugabe with the support of the army, Masunungure said.

He will not improve Zimbabwe’s human rights record, but may soften indigenisation laws to attract foreign investment, the analyst added.

If such changes took place in the country with a qualified workforce and rich mineral resources, “the economy could rebound spectacularly,” the Western diplomat said.