The legacy of Jairos Jiri, one of Zimbabwe’s most revered philanthropists and a national hero, has long been enshrined in the annals of the country’s history.

Often described as a man of "great compassion and courage," Jiri lived an illustrious and selfless life dedicated to uplifting the less privileged, a mission that spanned four transformative decades.

Yet, recent events emanating from within his own family have exposed a complex private life, threatening to cast a shadow over the legacy of this larger-than-life figure.

Born on June 26, 1921, in Bikita, Masvingo, Jiri’s journey was one of extraordinary determination.

Credited with establishing the first Black-led charity organisation for persons with disabilities (PWDs) in white-ruled Rhodesia, he blazed a trail of humanitarian sacrifice.

His path began in 1939 when, at the tender age of 18, he and his brother Mazviyo walked from Masvingo to Bulawayo in search of opportunities.

Jiri was profoundly moved by the plight of people begging in the streets, particularly those with disabilities, while he worked as a gardener, shop assistant, and cook for white families.

This deep-seated empathy, kindled amidst the hardships of a segregated society, compelled him to act.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Using his own meagre resources, he began caring for the physically challenged and the blind at his own residence in Bulawayo.

This humble beginning culminated in 1950 with the official registration of the Jairos Jiri Association, the first disability organisation led by a black person in Zimbabwe.

The founding committee, including Stephen Kwenda as secretary and Fabian Dururu as treasurer, embarked on a mission that would grow exponentially.

From a single centre, the association blossomed into a nationwide network of 16 centres.

This empire of compassion included schools and special schools for the deaf and blind, hostels, vocational and agricultural training centres, clinics, orthopedic workshops, and community-based rehabilitation programs.

Jiri’s work did not go unnoticed.

His acclaim was both local and international, adorned with numerous awards including an Honours Degree from the University of Rhodesia (1977), Member of the British Empire awarded by Queen Elizabeth II (1959), an audience with Pope Paul VI who presented him with a medal (1975), and the Freedom of the City of Los Angeles (1981).

At the time of his death in 1982, a nation in its infancy mourned a true pioneer.

He was accorded national hero status, though, in a testament to his famed humbleness, he had previously expressed a wish to be buried in his rural home of Bikita.

His legacy seemed secure, set in stone.

This was reaffirmed on August 11 of this year during Heroes Day commemorations, when President Emmerson Mnangagwa posthumously honoured Jiri among four nationalists, presenting their families with flags.

However, this public veneration has starkly contrasted with private turmoil, opening a Pandora’s box of familial discord.

The quiet narrative of a unified legacy has been disrupted by the public outcry of his outspoken widow, Betty Jiri.

She has lamented what she describes as neglect as the spouse of a national hero.

In May this year, Betty presented a wishlist to the government, arguing that she had contributed immensely to the Jairos Jiri Association.

“I fought a war of upliftment, disability empowerment and rehabilitation of persons with disabilities in the society in the country and the world at large,” she stated.

Her requests included a residential plot in Bulawayo, a solar-powered borehole for horticulture and fish farming, and a car to transport her to national events.

She falleged that her husband’s estate was distributed before the issuance of a death certificate in 2013, a process she claims happened without her knowledge, leaving her with nothing.

Her pleas garnered some response, with Doves Funeral Services offering a lifetime support package last month, including monthly grocery hampers and a paid-up funeral policy in recognition of her contributions.

Betty maintains she played a foundational role, co-founding the Association with her late husband.

Yet, this public narrative has not gone unchallenged from within the Jiri family.

Other members are not amused by Betty’s outbursts, though they are quick to exonerate her personally.

Instead, they point to an “external hand” they believe is manipulating the situation for selfish gain.

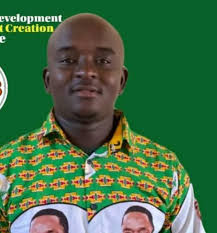

Speaking at the Gweru Press Club last week, Fungai Priscilla Jiri, the fifth daughter of Jiri’s last wife, Ethel, sought to clarify the matter.

“We are also here so that we can clarify certain matters that have emerged both within the family and the public space,” Priscilla said.

“As with many families, especially during times of loss and reflection, emotions may run high and opinions may differ.

“We want to assure the public that we are addressing all the issues internally with maturity, dignity and unity in line with the values our father instilled in us.”

Priscilla denied any internal family conflict, instead placing the blame squarely on external forces.

“We love and respect Mama Betty,” she said.

“In fact, everyone in the family is united and there is no conflict, but there are external forces who want to use Jiri’s name for personal aggrandisement and these are the real threats to the family.”

She did not name the external forces.

Priscilla provided a detailed account of Jiri’s complex marital life, painting a picture of a man who, despite his sprawling personal commitments, remained a pillar of strength.

Jiri married his first wife, Sophia, in 1943.

It was in the backyard of their four-roomed house that he first began accommodating PWDs, with Sophia washing and cooking for them.

The couple separated in 1958. Jiri then officially married Betty in 1963, only to divorce her in 1967.

Subsequent marriages to Georgina and then Mary followed before he finally married Ethel in 1974, with whom he had seven daughters and remained until his death in 1982.

Despite having five wives and 19 children, Priscilla insisted the Jiri name was one and the family remained “very united.”

“This moment is not about conflict but about preserving the legacy of a national figure who gave his all for Zimbabwe," she said.

"We remain united in honouring his memory and ensuring that future generations understand and celebrate his life works."