[ad_1]

By Thomas Chidamba

“Heritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations. Our cultural and natural heritages are both irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration.” — The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco).

Cultural heritage has been created by people and it has been created for people, hence the scope of heritage conservation and preservation should be in the hands of local people.

The term heritage is complex and has various interpretations, but it comprises cultural expressions of humanity and may be tangible or intangible, movable or immovable.

Tangible and intangible heritage is important to our country because it represents the living culture of communities, components of its inherent identity and uniqueness.

Heritage shapes people’s lives, feelings, emotions, hopes, memories and can teach us about cultures and people of the past, how they lived, the challenges they faced, and how they overcame them.

Therefore, heritage is a powerful lens through which we extract lessons from the past and those lessons can be applied to understand and tackle present and future challenges.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The value of cultural heritage is not in cultural manifestation itself, but in the wealth of experience and skills passed down from generation to generation. Hence, it is essential to preserve our cultural heritage to maintain our identity as a nation.

Colonial heritage management

During the 19th century, European kingdoms started to pay great attention to Africa and a lot of scientists, missionaries and explorers flooded Africa and what they saw astonished them because the African continent was full of impressive sights ranging from exotic animals, unique landscapes and indigenous people with their own culture and life, which were different from the Europeans.

As a result, the widely known “Scramble for Africa” began, leading to a colossal colonisation of the continent that left lasting impressions and far-reaching effects on indigenous people.

With the development of archaeology and heritage site management, most communities with attachment to cultural heritage sites were removed, often forcibly, in order to preserve sites and to make them more attractive to tourists.

Heritage management is a growing field that is concerned with the identification, protection, and curatorship of cultural heritage in its various forms in the public interest.

Cultural heritage is central to protecting our sense of who we are as it gives us an irrefutable connection to the past social values, beliefs, customs and traditions that allow us to identify ourselves with others and deepen our sense of unity, belonging and national pride.

However, heritage management and archaeological research in Zimbabwe have been by-products of colonialism.

Management of the cultural heritage and archaeological research were done without the involvement of the indigenous people because the colonisers failed to understand fully the cultural significance of the heritage and to appreciate its value to local communities.

This exclusion resulted in locals shunning heritage activities despite them having maintained these cultural sites intact until the coming in of colonisers.

Before colonisation, heritage sites and cultural paraphernalia were kept intact through some form of management by indigenous people who used taboos and restrictions to protect them.

But colonialism brought a new paradigm of heritage management as cultural heritage sites became government property and accessible to tourists who paid to enter while traditional rituals were banned as locals were alienated from their cultural sites.

This new way of cultural heritage management led to the criminalisation of people in the surrounding community who were barred from cultural heritage sites so as not to disturb visitors.

According to Ndoro and Wijesiriga (2015), the colonial heritage management system appears to have acquired a strong ally in the international institution that seems to reinforce the heritage definition, practice system emanating from colonial period.

Colonisation brought its interpretation of African history, which was largely influenced by Eurocentric ideologies that viewed Africa as a dark continent. African patterns of cultural development, and ways of life were forever impacted by the change in political structure brought about by colonialism.

Post-independence heritage management

In 1980, the country got independence to mark the end of years of British rule and ushered a new political environment that placed new responsibilities on heritage managers.

With the fall of colonialism in our historical discourse, high hopes were that indigenous archaeologists were going to pay more attention to implications of their interpretation of the past in order to lay critical ground for assessing the effects of Eurocentric thinking in cultural heritage and archaeological research.

With the dawn of a new era, communities with spiritual and physical attachment to cultural heritage near them also yearned to be involved in the management of cultural heritage sites.

However, the nature of their involvement conflicts with professional heritage management because the philosophy of heritage management alienates local people from their past.

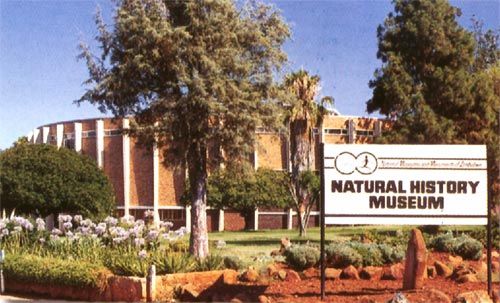

This conflict brought a new challenge for heritage managers, hence the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) has a role to play to enable the negotiation of heritage management practices and development of culturally appropriate protocols.

This will make heritage management practice depart from colonial construct and shift the role of institutional practices to focus on careful representation and articulation of objects, contested narratives and recognition of community heritage management practices.

In this independent country, NMMZ should lead the decolonising of heritage management to accommodate communities associated with cultural heritage and reorient history of Africa that is sometimes painted in the negative.

Colonial heritage legislation

NMMZ is the national culture and heritage premier agency established by the National Museums and Monuments Acts of 1972, to look after the cultural heritage of the country on behalf of the people.

While national consciousness to the significance of heritage is clear, it needs to be noted that the legislation mandates NMMZ as the legal custodian of the country’s cultural heritage. The colonial Act and does not make any specific mention of communities which makes, in some cases, community consultation by NMMZ optional, thereby creating a fertile ground for conflict between the regulator and its stakeholders because heritage preservation and cultural management in Africa is a colonial creation and did not take onboard the expectations and aspirations of local communities.

Colonial heritage management practices were used by the colonial regime to undermine indigenous cultures while highlighting the positive impact of colonialism.

Now four decades after independence, colonial tastes still prevail in heritage management practice. The shadow of colonialism has stuck with us, hence it is time to shrug it off and move towards the fostering of people-centred heritage management practice.

Conclusion

The treasure of historical-cultural relics, landscapes and intangible cultural heritages left by our ancestors is not just a great and valuable asset, but also a resource for sustainable development that, if protected can promote the values of national cultural heritage and bring practical benefits to local communities.

Heritage is an irreplaceable resource, and in order to address the relationship between heritage conservation and community participation it is encouraged that NMMZ takes a people-centred approach as an integral element of heritage management.

Engaging communities is about strengthening their ability to participate meaningfully in the process of making conservation and management decisions for themselves and their heritage.

Community participation in heritage management

Cultural relics are from the past living in the modern era must be able to relate to the people and become part of contemporary life. In the process of implementing heritage conservation projects, it is necessary to raise awareness and understanding of the value of the heritage for the local communities to help them understand their role and responsibility in the protection of their heritage.

Practical actions such as training members of the community knowledge about the heritage help process of promoting and conserving the heritage

It is understood that when communities try to promote the local heritage without proper regulations and help from professionals, it could easily damage the site and potentially degrade the values of the cultural heritage. Therefore, it is a necessity to have that co-operation between NMMZ officials and local communities when dealing with cultural sites and heritages.

- Thomas Chidamba is a journalist and a qualified archaeologist based in Harare. He writes here in his personal capacity. He can be reached on [email protected].

[ad_2] Source link